30 years later, friends and family remember the impact of three student deaths on their lives

30 years ago, a car accident took the life of three Talawanda teens. Today, their friends and family still remember them and the impact they had on the community.

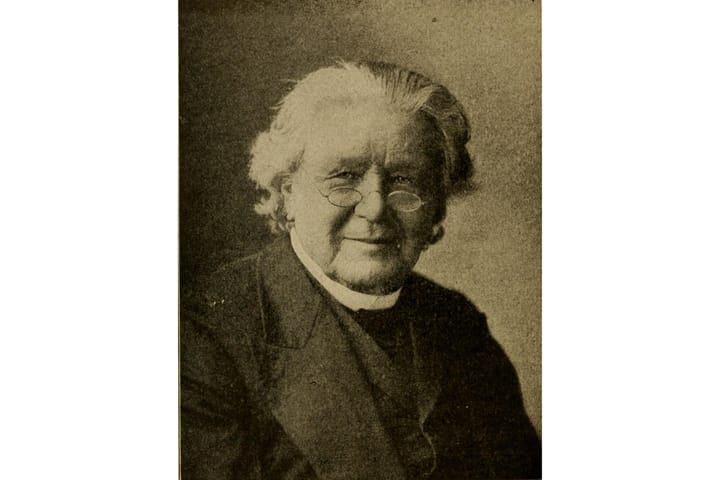

By age 15, Taylor Metcalf was already signing his autograph at a Reds game in Cincinnati — not that he was a member of the team.

Taylor had been accompanying his uncle, a sports photographer, as he covered the game, remembers Lynn Metcalf, Taylor’s mom. When Taylor went out to the tunnel, some fans mistook him for a player and asked for his autograph. He happily signed for everyone who asked, until his uncle caught him, Lynn Metcalf said.

That year was ultimately Taylor’s last. On April 22, 1995, he and two other Talawanda High School freshmen, Stephen Meade and Joshua Peterson, died in a car accident. Now, 30 years later, their memory lives on for friends and family alike.

A black lab and pumpkin pies

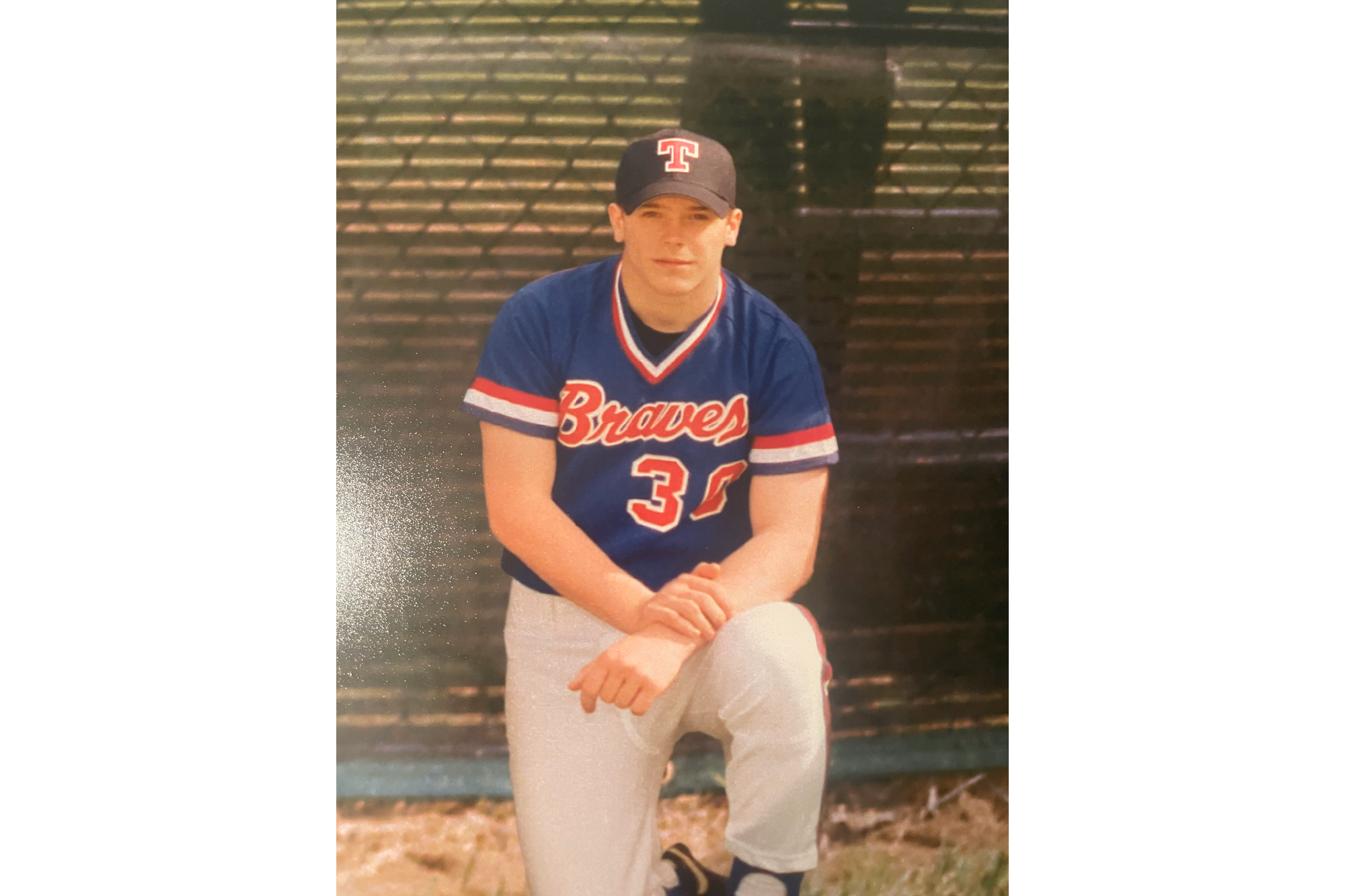

The thing to know about Josh, said Chad Chenoweth, who was a close friend of his, is that he was a big kid in both stature and heart.

“His personality was backed by just love,” Chenoweth said. “He would do anything for his friends, and did anything for his friends. He was a great athlete, a great son, a great friend.”

Chenoweth and Josh lived near each other in Hanover Township and became fast friends on their bus rides together. When Josh moved even closer, Chenoweth said they almost always got off at each other’s houses and spent the afternoons in the woods, on their bikes, hanging out with their other friends in the neighborhood.

There was one barrier to hanging out with Josh, though: The dog.

Tucker was a black lab who lived halfway between Chenoweth and Josh’s house, and he had an attitude, Chenoweth remembers. Tucker liked to chase Chenoweth on his bike. Josh, on the other hand, was taller than most kids their age. Tucker wouldn’t mess with him.

“Josh would come out of his way to meet me down there … because that dog wouldn’t get anywhere near him,” Chenoweth said. “He thought it was funny that the dog wouldn’t chase him, but he kind of was my protector, you know?”

Chenoweth still thinks of Josh when he sees a black dog today, 30 years after Josh’s death. For Janelle Allen, who lived next door to Josh, it’s pumpkin pie that reminds her of him.

Every Halloween, the Allens would get pumpkins to carve, pumpkins for decoration and pumpkins for baking pies. One year, they got an especially large pumpkin, and she went next door to ask Josh for more baking ingredients because they didn’t have enough. Instead of just handing over the ingredients, Josh came over himself, and Allen thinks now they must have baked 11 pies that day.

“He was really shy until he got to know someone,” Allen said. “He was pretty reserved, but not awkwardly.”

Josh was an athlete, like Taylor and Stephen. His main sport was baseball, and he was the one who dared Allen to try out for softball herself. She would catch for him sometimes so he could practice his pitches.

On the night of the accident, the girls softball team was away for a double header, Allen remembers. The boys baseball team was at home. Josh’s mom would normally pick her up from events since they lived so close, but she knows someone else must have picked her up that day. No one on the softball team knew that the three boys had died until they got home.

““For most people, it was just devastating, it was sort of like … the feeling of it on a smaller scale of course was like when the Twin Towers were bombed,” Allen said. “So much loss, so quickly, completely unexpected, totally heart wrenching. Life as we all knew it was never the same.”

10-foot baskets and mushrooms

By the time Stephen got to high school, he had honed in on basketball.

“Like any young kid, number one, he was having fun,” Pat Meade, his father, remembers now. “He liked the game, he liked being part of the team, and he was pretty competitive.”

Stephen was one of six siblings. To his younger brothers, he was like a mentor, Meade said. During the spring that he died, he’d been trying to teach his four-year-old brother how to make a 10-foot basket.

On April 19, less than a week before the accident, the Oklahoma City Bombing happened. Meade remembers seeing Stephen’s eyes welling up as he watched the news, asking who could do that to children.

“That sums up part of who he was,” Meade said. ‘He had that empathy, as well as being a sports person with a drive and a competitiveness and a desire to be successful. There was also underneath that a heart that would not understand why people would hurt people.”

Jay Berenzweig knew Stephen from a very young age: Stephen’s mom babysat Berenzweig when he was still four or five. When Berenzweig transferred from private school to Talawanda in sixth grade, it was Stephen especially who made him feel welcome.

“He was an outgoing kid,” Berenzweig said. “I wouldn’t call him shy in the least bit. He was a funny kid; he always had something funny to say. I always think about that, and it puts a smile on my face.”

Stephen and Berenzweig were part of a large group of friends at the time. It was before cell phones, and they were always outside getting up to something new. Meade said they were a tight-knit group even before Stephen, Taylor and Josh died, and they stuck together to support one another in the months and years that followed the accident.

“They were constantly on the go, doing things, going places,” Meade said. “I think the day that he died, him and a group of them were mushroom hunting.”

The accident was in the middle of baseball season. At every game for the rest of the year, Berenzweig remembers the coaches telling them to lace up for Josh, Stephen and Taylor, even though Stephen wasn’t on the baseball team.

“Steve was like a brother to me, and it was tough,” Berenzweig said now. “It’s hard to remember everything, but I just know it was a shock, three people ripped out of your life like that. Everyone experiences tragedy, I get that. But at that young age, it set pretty hard on myself and I’m sure a lot of other close friends, as well.”

Gretzky and the rodeo

By the time he reached high school, Taylor was involved in everything — football, baseball, whatever team he could get involved with. His first and longest love, though, was hockey.

Lynn Metcalf remembers him falling in love with the sport as a 4-year-old. They lived in Delaware at the time. She told him he could start hockey once they moved back to Oxford when he was five, but when they passed an ice rink in Delaware one day, he was determined to play.

“He talked me into it,” Metcalf remembers. “He’s really good at talking me into things.” She saved grocery money to buy his equipment and took him to a learn to skate program with parents. Taylor chose 99 as his number for his love of Wayne Gretzky.

Jim Kuykendoll was friends with all three of the boys who died and remembers them all as people with competitive spirits and a desire to lead. In Taylor, Kuykendoll also saw a desire to try everything possible, up to and including rodeo. When they weren’t at practice or school, they were with each other.

“I was always at Taylor and Steve’s house and vice versa,” Kuykendoll said. “It was just constant. We were very on the go. We would ride our bikes all over town.”

Metcalf first got the news that her son had died when a cop came to the door to tell her. She was single at the time, and the officer wouldn’t leave until her neighbor came over to be with her.

It didn’t take long for others to show up, too.

“The house started to fill up with kids, friends,” Metcalf recalled. “I can’t tell you the grief.”

While no parent can prepare for their child’s death, Metcalf said it was less isolating because of the support. She, the Meades and the Petersons all supported one another, but she was most encouraged by Taylor’s friends.

“I could never say enough about those kids, because we all just grieved together,” Metcalf said. “Those kids just had such courage to bond together with love and compassion and care for each other. Because of them, because of that is really, I think, why I survived.”

Grieving and growing

Kuykendoll first heard that Josh, Taylor and Stephen had died in a car accident after walking to a party with friends. Within the next couple days, he remembers being called by the Dayton Daily News to give a quote. Everyone had to grow up quickly, he said.

The loss is difficult to explain to people who didn’t go through it, Kuykendoll said. “I talk with our group of friends still today about it occasionally … We have that connection, but it’s hard to talk about it with anyone else other than the people in our close circle of friends.”

Metcalf lives in Montana now, but she still hears from Taylor’s friends, especially around April 22 each year. The week leading up to the date is the hardest, and few people in Montana know about her loss.

To Allen, it seemed like everyone handled the grief in their own ways as they grew up and graduated. The halls got especially quiet for the rest of freshman year, she said.

“When human beings go through a hard time, usually they call it faith, family and friends,” Allen said. “Faith, family and friends to help pull you through hard times and process your grief.”

Meade spoke at the boys’ grade’s high school graduation, and he told them all what their support had meant to him as a parent.

“That group of kids hugged us back to life,” Meade said. “For those three years they were still in high school, if you saw any of them, you got a hug. They just cared so much.”

For more than a decade, the three families maintained a scholarship for student athletes. The Meades gave out a freshman basketball award each year, and the Taylor Metcalf Fund was also established to support local students interested in hockey. The sport has a high barrier to entry with equipment fees, and the fund awarded nearly $20,000 in scholarships last year.

Emily Greenberg is a board member with the fund and was a friend of Taylor’s in school. She remembers Miami University’s Interfaith Center opening its doors to students after the accident, and sitting on the football field on the first day back to school after the accident. School was in session, but the day was focused on mourning, not instruction.

“At 14, 15, you don’t know what to do. You don’t know what to say. You just know how you’re feeling,” Greenberg said.

Honoring memory with a tournament

This May, the Taylor Metcalf Fund is holding its third annual adult hockey tournament. The event will run May 2-4, and the proceeds go toward supporting student hockey players with financial needs.

In 2023, the tournament attracted more than 70 players, and last year it rose to nearly 100. This year, board member Emily Greenberg, who was friends with Taylor in school, said they’re expecting slightly less than in 2024, and the tournament will have six teams, each sponsored by businesses.

The games will be free to watch, Greenberg said, and people interested in playing can sign up for a waitlist in case others can’t make it.

“Taylor doesn’t have a grave here in Oxford,” Greenberg said. “This is our way of remembering Taylor.”