Funding Education: Talawanda funding could be at risk in next state budget

Ohio Governor Mike DeWine's budget proposal didn't include drastic cuts to public education funding, but other lawmakers have signaled a move in that direction this budget cycle.

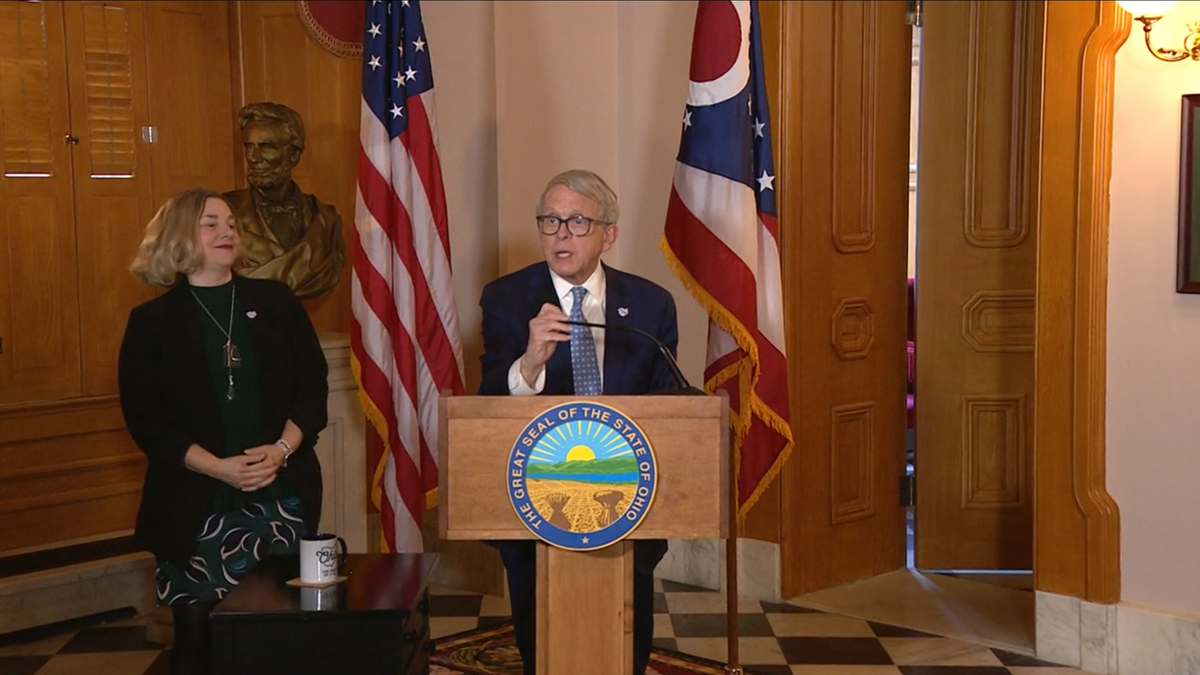

As he presented his Executive Budget proposal Feb. 3, Ohio Governor Mike DeWine put a heavy focus on children and education. DeWine indicated that he would try to preserve a public education funding plan passed four years ago to fix the previous state funding which had been deemed unconstitutional, but that’s easier said than done.

As the governor sets up for a potential showdown with other legislators during the budget process, schools like the Talawanda School District may get caught in the middle. At stake: millions of dollars in state funding each year, which could have a significant impact on Talawanda if the funding doesn’t continue.

This story is the third in a series on school finances and the Talawanda School District.

What’s the current status of state education funding?

To understand Ohio’s current school funding model, you have to go back to 1997. That year, the Ohio Supreme Court ruled that the state’s public education funding model was unconstitutional. The state constitution requires that the legislature will “secure a thorough and efficient system of common schools throughout the state,” a requirement that was not being met because school districts were too reliant on property taxes, resulting in inequitable outcomes based on district wealth.

For decades, lawmakers tweaked state funding and proposed solutions to improve state funding. The bipartisan Cupp-Patterson Plan, introduced in 2017, was drafted by then-representatives Bob Cupp, a Republican, and John Patterson, a Democrat. However, it took numerous revisions and four years for the bill to finally pass as the Fair School Funding Plan in the state’s 2021 budget.

Republican Sara Carruthers, who represented Oxford and Hamilton in the State House at the time, cosponsored the bill, which had passed in the house and made it to a senate committee during the previous legislative session.

Under the Cupp-Patterson plan, every district receives a base cost funding. The state calculates a base cost per pupil for each school district and subtracts the local contribution per-pupil from that measure, leaving the base cost per pupil paid by Ohio.

Districts may also receive what’s known as the guarantee. If the calculations used to determine state funding would result in a sudden drop in support year-to-year or a district’s enrollment decreases, it may receive guarantee funding to make up the difference.

Talawanda Treasurer Shaunna Tafelski explained that the mechanism prevents districts from receiving less state funding than either the previous year or the previous three-year average, whichever value is higher. This year, Talawanda is set to receive nearly $8.8 million in state funding, $2.2 million of which comes from the guarantee.

The Cupp-Patterson plan had a six-year implementation period. The first two years were partially funded, and the next two were fully funded. Years five and six are being decided in the current budget cycle, and the plan’s overall implementation would cost a total of $2 billion if followed through, according to reporting by the Statehouse News Bureau.

Click here for links to more stories on Funding Education:

What are state lawmakers saying about public education funding?

While introducing his executive budget proposal Feb. 3, DeWine said his biennial budget would include a phase-in of the final two years of the Fair School Funding Plan. He added, however, that his plan “allows us to phase out the funding of empty desks in schools” by “reducing funding guarantees.”

Kimberly Murnieks, director of the Office of Budget and Management, said the guarantee would be reduced to 95% in 2026 and 90% in 2027 under DeWine’s proposal.

DeWine acknowledged the uncertainty with the budget, however, particularly given Ohio House Speaker Matt Huffman’s repeated comments that he wants to reduce public school funding from the state. “This is an area … where the legislature will do many, many things between now and when this bill finally gets to [my] desk and I sign it,” DeWine said.

Huffman has called the Cupp-Patterson funding model “unsustainable,” and one Republican member of the House Finance Committee criticized the funding formula for not awarding “the merit of outcomes,” according to reporting by the Ohio Capital Journal. DeWine’s budget would allocate a total of $12.4 billion to state schools in fiscal year 2026 and $12.6 billion in 2027.

According to reporting by the Statehouse News Bureau, Huffman has claimed that the legislators who voted to pass the Cupp-Patterson plan “can’t bind four years later what a General Assembly can do.”

DeWine’s budget did not include reductions in the state’s private school scholarship program, which cost nearly $1 billion in fiscal year 2024. That included more than $400 million in EdChoice expansions providing vouchers for parents to send children to private schools. Reporting by the Ohio Capital Journal found that while private school voucher spending increased significantly, private school enrollment only increased by 2%.

For Matt Wyatt, a Talawanda Board of Education member and the district’s legislative liaison, the idea of not fully funding the Cupp-Patterson plan is unconscionable.

“If you’re a legislator, and you’re voting to not fulfill the promise to your public schools, you are stabbing your local school district in the back,” Wyatt said.

Republican state lawmakers have not suggested implementing cuts to the private school voucher program yet during this budget cycle. Wyatt said public school officials need to recognize that school funding is a partisan issue, or else they won’t be able to adequately advocate for themselves.

Wyatt previously served on a school board in Kentucky for 10 years. During his time as a board member in Kentucky, Wyatt said he saw voters from across the political spectrum come together to support public schools, organizing statewide against legislation that would have expanded charter schools. Kentucky’s school funding structure was also deemed unconstitutional at one point, but the state began to climb in national education rankings after passing substantial reform measures. Last November, Kentucky voters rejected a ballot measure to expand a school voucher program.

In Ohio, Wyatt sees school voucher programs as subsidizing private education. If public schools lose funding, it could lead to worse educational and workforce outcomes in the long term, he said.

“School funding in this state is the number one crisis,” Wyatt said. “There’s nothing else — nothing else — that comes close to the future of Ohio … and until we get on the same page with that and fight really hard and show some consequences at the ballot box, it’s going to get worse.”

How does state funding and the guarantee impact Talawanda?

Tafelski has been treasurer for Talawanda for multiple budget cycles, and she said this is the first time the governor has suggested any openness to limiting the guarantee.

“From my standpoint, we need to be very cautious until we have his final budget,” Tafelski said. “We don’t want to be adding on, unless it’s required for a student’s specific learning needs. I’m hesitant on adding additional programs, I’m hesitant on bringing on anything new.”

DeWine’s budget proposal will go through the state house and senate multiple times before making its way back to his desk, likely in late June. The state is required to adopt its two-year budget prior to July 1.

Currently, the State House is considering revisions to the budget. Republican State Representative Diane Mullins, who represents Oxford and Hamilton, did not return a request for comment.

Republican State Senator George Lang said it’s premature for him to comment on specific budget items because of the potential for significant changes before it comes in front of the state senate. He expects to see a house draft in the next six to eight weeks.

“Once it comes out of the house over here, then we’ll take a deep dive and see if the house makes any changes,” Lang said. “In general, though, I’d like to keep funding for public schools — and all schools — at some healthy levels. My goal is to increase school choice so that parents can choose whether they want to use public dollars to send their kids to a private educational institution or a public school.”

Lang said he had not looked into any comments from Speaker Huffman regarding cuts to the current public school funding plan. No constituents had reached out to him about education funding in the current budget cycle as of Feb. 12, he said, though he expected that to pick up once the budget bill makes it to the senate.

If the guarantee is stripped away entirely, or if the 5% reduction in 2026 impacts districts unevenly across the state, Talawanda could lose up to $2.2 million in funding per year. A representative for Governor DeWine’s office did not respond to requests for clarification regarding how the guarantee reductions would be implemented.

Tafelski’s most recent five-year forecast showed the district ending 2029 with a 255-day cash balance. If the district loses the entire guarantee this year, Tafelski estimates that the 2029 cash balance could drop to 188 days. The district could dip below a 90-day balance, the district’s minimum, two years earlier if the guarantee goes away.

While the district’s Board of Education has discussed the potential for adding new staff positions including a school psychologist and new elementary school teachers, Tafelski said her priority is to avoid changes to the school budget until the state funding is made more clear.

New positions ultimately require board approval, and Wyatt said he agrees that the district needs to be cautious. Wyatt supports bringing back expanded busing, which the board voted in favor of for the 2025-26 school year, but cautious spending in the current budget cycle could mean other needs or wants have to go unmet.

“We have to resist the temptation to solve every problem, because we don’t have the resources,” Wyatt said. “Even if we have them right now, we should not feel confident that we’ll have them two years from now.”