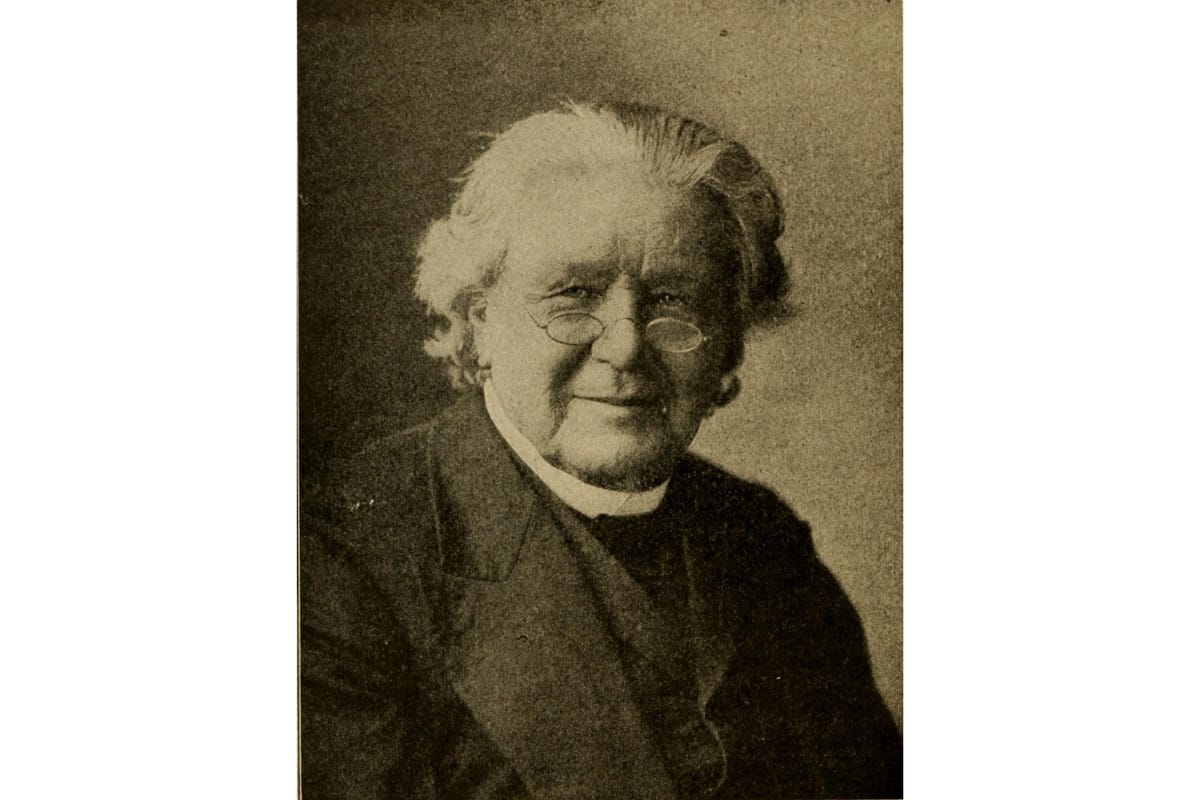

Local Legends: America’s apiculturist

Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth has a place in both Oxford history and American beekeeping history for pioneering the Langstroth hive..

Something was buzzing in the mind of Rev. Lorenzo Lorraine “L.L.” Langstroth that would eventually earn him the title of “the father of American beekeeping.”

Langstroth was born in Philadelphia on Christmas Day 1810 to John George Langstroth and Rebecca Amelia (Dunn) Langstroth.

Langstroth developed an early fascination with insects, building the foundations for his future expertise on the subject. He conducted his own experiments, including burying breadcrumbs in dirt to examine how ants reacted to the introduction of food into their habitat.

His aristocratic parents weren’t pleased with this interest of his. One biography states that in an attempt to redirect him from “wast[ing] so much time” with his “strange notions,” they denied him access to books on entomology.

Perhaps his parents were successful, as Langstroth had largely abandoned his interest in insects by his formative years. He entered Yale College in 1827, attending the institution’s Divinity School. Langstroth worked as a math tutor to support himself through college following his father’s financial failure, and he graduated in 1831.

Langstroth spent time as a Congregational minister in New England after graduating and married Anna Mary (Tucker) Langstroth in Connecticut in 1836. His son was born the next year, and the couple had two daughters in the 1840s.

The rediscovery of Langstroth’s passion for insects also came in 1837, when he purportedly visited a friend who kept bees in the attic of his house. Upon seeing a jar of honey, Langstroth inquired about the bees, and his friend showed him the hives.

As a result of the intense curiosity sparked by the bees, Langstroth immediately purchased two hives of his own. Now an adult with no one to hinder his access to books related to his interests, Langstroth sought out all of the published works related to beekeeping he could get his hands on, quickly becoming an expert on the topic.

Langstroth took over as the principal of Greenfield High School for Young Ladies in Greenfield, Massachusetts starting in the 1839-1840 school year. With a bout of ill health, one of many that would plague him throughout his life, he stepped down as pastor and slowly began to increase the number of hives he kept.

In 1848, Langstroth moved back to Philadelphia and began building experimental beehives with his wife’s help. Within only a few years he would revolutionize the apiarist industry.

Langstroth developed the moveable frame beehive in 1851. Each frame could be pulled out of the larger hive, allowing beekeepers to harvest honey and check on the health of the bee colony without killing the bees while also keeping the bees contained in the hive.

The hive was based on the principle of “Bee Space,” another major breakthrough of Langstroth’s. From observing bees’ habits, Langstroth determined that the minimum space for a bee to build a comb, bee space, was 1/4 to 3/8 inches.

Langstroth obtained a patent for his moveable frame hive in 1852, and he published the groundbreaking book “The Hive and the Honey-Bee” in 1853 as a guide for beekeeping.

Langstroth soon ran into trouble with patent rights, business dealings and fraudulent claims that others had invented the moveable frame hive before him. This led to a tumultuous period characterized by financial strain and legal battles, coupled simultaneously with more health problems. Anna successfully obtained a reissue of Langstroth’s patent on his behalf in 1866 when he was too sick to do so himself.

The Langstroths relocated to Oxford in 1858 and resided at what is today known as Langstroth Cottage at the present intersection of Western College Drive and Patterson Avenue. The home, and land, was purchased for his family by his brother-in-law Aurelius B. Hull. Langstroth’s mother accompanied them to Oxford, where she died on Oct. 12, 1860.

With John’s assistance, Langstroth imported Italian bees to Oxford and continued his experiments, selling $2,000 worth of Italian queens in one season. They employed local carpenters, such as Samuel Gath, to build the hives. The Agricultural Schedule of the 1870 Census showed Langstroth as owning a 4-acre farm with a single horse and 1,500 honey bees.

John died that same year and was buried back East in Greenfield, Massachusetts. Langstroth would also lose Anna in Oxford, who died three years later on Jan. 23, 1873. In his later years, Langstroth reportedly enjoyed taking walks from Langstroth Cottage to Oxford Cemetery to visit his wife’s grave.

With Langstroth’s health again declining, by this time he was subject to seizures, he gave up large scale beekeeping in 1874. However, he continued to experiment and remained involved with the beekeeping industry.

An 1874 letter from Mary Ann (Smart) McFarland to her husband Robert White McFarland recorded, “I went over to Mr. Langstroth's for an hour. Mr. Langstroth was in one of his talkative moods … he showed us some of his ancient books.”

Langstroth served as the keynote speaker for the annual conclave of the North American Beekeepers Society in Cincinnati in 1880 and published articles on his experiments in the American Bee Journal.

Having moved to Dayton, Langstroth was delivering a sermon on Oct. 6, 1895 when he complained of feeling ill. He sat down in a chair where continued to speak before suddenly dying while still in the pulpit. Langstroth was buried in Woodland Cemetery in Dayton.

His legacy was long remembered in Oxford. In 1976, The Butler County Beekeepers Association and the Oxford Museum Association commemorated Langstroth with a program and a pamphlet, “The Bee-Man of Oxford and Langstroth Cottage” published by Oxford Printing Company. This month’s Oxford Bee Festival was partially to honor his legacy.

Langstroth was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2007.

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects.