Local Legends: Freedom and glory

For decades during the 19th century, the Jones family of Butler County helped fugitive slaves escape prosecution on the Underground Railroad and fought for the freedom of all during the Civil War.

Rumors of hidden passageways, underground tunnels and secrets held by old houses characterize contemporary notions of the Underground Railroad. However, little verifiable information regarding the network of “stations” that led escaped slaves to freedom can be corroborated due to the clandestine and illegal nature of the system.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 pushed the freedom line north from the Ohio River to Canada for slaves escaping from the American South. It also made it a crime to assist escaped slaves in their evasion of slave catchers and flight to freedom.

One of many routes between the Ohio River and Canada brought fugitive slaves through Butler County under the protection of conductors Jack Jones and his son, John S. Jones.

The elder Jones lived on a tenant farm on Millikin’s Island, later known as Campbell’s Island, located between Hamilton and New Miami along the present day Third Street Extension. Jack Jones likely helped fugitive slaves hide on the island, as well as at his residence near the present intersection of High Street and Witt Way in Hamilton.

According to John Jones’ obituary, Jack Jones used his “old jolt wagon with a linen cover thereon” to secretly transport slaves north from Hamilton. John Jones assisted his father in the illegal endeavor.

John Jones purchased a 60-acre farm on Booth Road in Oxford Township on Feb. 29, 1859. This provided an additional waypoint for the runaways, who were now instructed by Jack Jones to make their way up the Junction Railroad line to the farm.

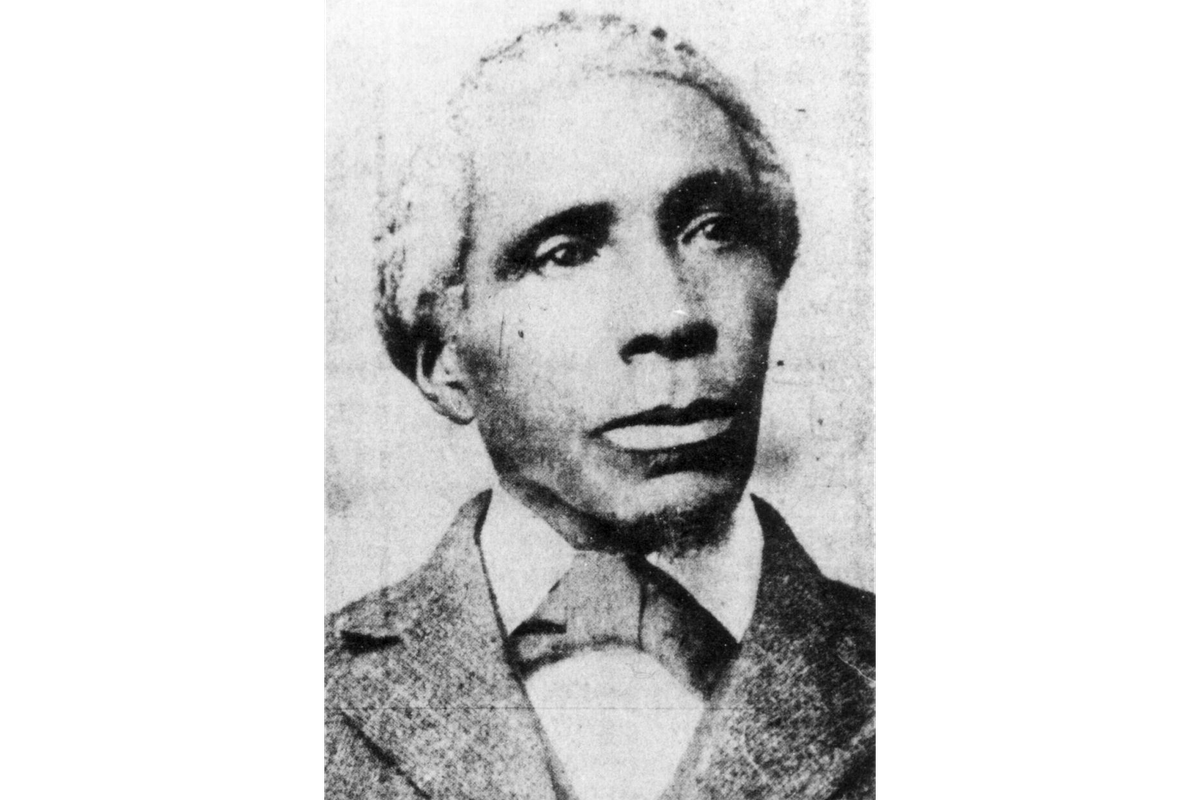

The younger Jones was born in October 1819 in Butler County. He married Lucinda Giles in 1838, and the couple raised at least five children until Lucinda’s death. Jones married Ellen V. Fletcher, maiden name unverified, and appears to have had additional children.

Jones also has another important claim to local history. In 1852, he witnessed two horses killed by a train while farming on Millikin’s Island and testified in court as part of the lawsuit that followed. This was the first Black citizen to testify in a Butler County court and was only possibly due to the recent repeal of Ohio’s “Black Laws” in 1849.

Jones guided the freedom seekers on the next leg of their journey, conducting them to either the Quaker community at West Elkton, Ohio — a major regional hub for Underground Railroad activity — or to Richmond, Indiana.

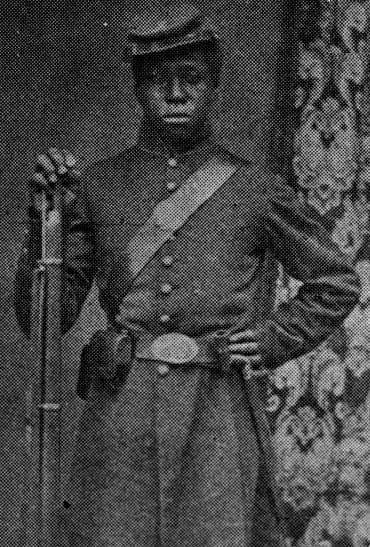

As the need for more Federal troops grew during the American Civil War, regiments composed of all Black troops, with white commanding officers, began to be stood up. The second of these was the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the unit that was immortalized in the 1989 motion picture “Glory.”

Robert J. Jones, son of John Jones, enlisted in the unit. Robert’s brother, John M. Jones, enlisted in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, a sister regiment to the 54th formed from overflow Free Black and escaped slave recruits showing up to enlist.

Robert participated in the unsuccessful and devastating assault against Confederate entrenchments at Fort Wagner, South Carolina on July 18, 1863. John’s unit was not involved in the battle but was involved in the successful siege of Fort Wagner that followed.

Both regiments continued carrying out operations in the Charleston area before deploying to north Florida in 1864. It was there, during the Battle of Olustee, where Robert was either killed in action or taken prisoner and placed in a camp where he later died — sources disagree.

John’s regiment entered combat again at the Battle of Honey Hill before Joining William Tecumseh Sherman’s famous March to the Sea. He survived the war and discharged at the rank of corporal, having achieved the rank for a second time after being reduced to private for being absent without leave.

Following the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the war, the Jones Family was able to return to farming, having done their duty to their nation.

Little is known about the post-war lives and fates of Jack and John M. Jones.

John S. Jones continued working his 60-acre farm for the remainder of his life. He died on the farm on Aug. 20, 1898 after being thrown from a wagon when its team of horses were spooked by a falling bundle of shingles. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Hamilton.

The Jones Farm remained in the family following his death. The farm’s log house, strongly evidenced as being a stop on the Underground Railroad, remained intact at 5643 Booth Road until being destroyed by fire in 1974.

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects.