Local Legends: The persistent dream

O.T. Jackson was born in Oxford, Ohio, but his life and career took him all across the state and eventually to Colorado, where he started his own settlement.

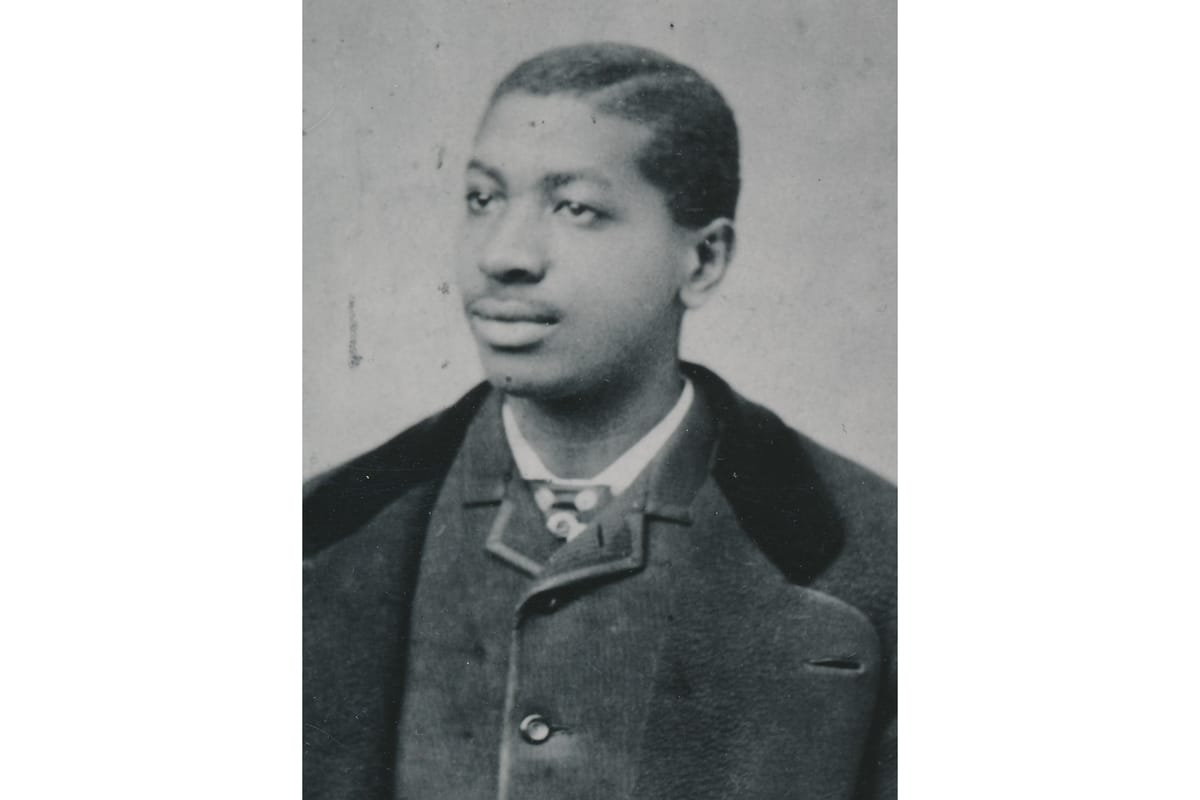

Oliver Toussaint “O.T.” Jackson was born in Oxford on April 6, 1862, the son of Hezekiah and Virginia Caroline (Chavous) Jackson. Although his parents were born in Virginia in the 1820s, they never lived a day as slaves, having both been born into a free Black community located in Charlotte County, Virginia.

His parents married on April 19, 1847, and relocated to Oxford in 1853. The family lived in the predominantly Black populated north part of Oxford, where they raised their 8 children.

Tragedy struck the Jackson Family in 1868. Jackson’s mother gave birth to twin boys, Edward and Edwin Jackson, but she died suddenly of apoplexy, likely a stroke, 6 weeks after their birth. The following month, both twins died of cholera a day apart from each other.

Jackson spent his early years in Oxford, but by age 18, he had moved to Cleveland, Ohio. The 1880 census listed him as a servant for a white family in Cleveland.

Jackson became associated with the Gazette Publishing Company, which his brother John H. Jackson co-founded, in 1886. The company published the Cleveland Gazette, a Republican funded and backed newspaper and the first post-Civil War Black newspaper in Cleveland. The following year, Jackson left to be the business manager for the Democratically aligned Cleveland Globe.

The American West promised to be a land of excitement and progress and held the promise of a fresh start and a chance for prosperity in the minds of westward settlers. Jackson left the newspaper business for the restaurant industry in 1887 and arrived in Denver, Colorado by 1889.

Sadie (Cook) Jackson, a native of Michigan, married Jackson on Sep. 5, 1889. Jackson’s brother, the aforementioned John H. Jackson, and niece, Jennie Jackson, joined the couple in Boulder prior to the 1900 Census.

Sadie Jackson died on Feb. 1, 1904 and was taken back to Michigan for burial. Jackson remarried on July 12, 1905, wedding Minerva (Matlock) Jackson.

Jackson was deeply inspired by Booker T. Washington’s book “Up From Slavery,” especially the ideas of Black land ownership expressed in the work. The politically minded Jackson saw this as a means by which Black people, specifically former slaves, could escape the intolerance, racism, and abuse perpetrated against them in the post-reconstruction era.

He soon devised a plan to create an all-Black settlement in rural Colorado. Jackson was first appointed Messenger to the Governor in 1909, and his political savvy and access to government officials likely aided him in the execution of his plan.

Jackson formed the Negro Townsite & Land Company in 1910. The company ultimately failed, but that didn’t hinder him in his pursuit to establish his community. Jackson founded Dearfield, Colorado in 1911. Its population consisted of the nineteen pioneers who had trekked to the vacant rural site.

Conditions were hard at first, as the pioneers had to build everything from the ground up. They initially slept in dugouts as they worked on constructing the first buildings. Within four years, forty-four log houses stood in the agricultural based settlement.

Jackson had initially encountered some difficulty in finding settlers to accompany him to Dearfield — many Black citizens distrusted Jackson and his Democratic politics. However, once success was proven, the population of the community continued to grow and peaked at an estimated 300 residents between 1917 and 1921.

Using his restaurant experience, Jackson opened and operated the Dearfield Lunchroom, which became the town’s community center. Eventually, the town grew large enough to have two churches, a boarding house, a hotel, a school, a coal and lumber yard and a factory.

Jackson also went through the process of gaining title to the land upon which Dearfield had been constructed. He succeeded in this endeavor, and President Woodrow Wilson signed the land patent for the 320 acre community on June 5, 1918.

Although Dearfield appeared to be an unmitigated success up to the 1920s, it proved to be highly susceptible to drought conditions leading to crop failure and corresponding economic instability. The hardest blow came in the 1930s when the Dust Bowl completely destroyed Dearfield’s fields and crops.

Most Dearfield residents abandoned the town and headed back to Denver or other large cities, seeking work that would support their families in its place. By 1940, only 12 residents remained, including Jackson and his family.

Jackson didn’t give up, trying to convert the town into the Valley Resort, a vacation spot for Denver’s Black families. When this failed, Jackson unsuccessfully attempted to sell Dearfield to the federal government for use as an internment camp for Japanese-Americans in the early part of World War II.

His wife died soon after on Dec. 14, 1942. Jackson himself died on Feb. 8, 1948 at the age of 85.

Dearfield was partially demolished and became a ghost town, with only a few heavily dilapidated buildings still remaining. Dearfield again garnered national recognition in 1995 when it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects.