Media Matters: The sound of music … Edison to Elvis

Technological revolutions in sound recording have driven revolutions in the way we connect with the world, especially music, writes columnist Richard Campbell.

I remember the moment I got interested in music. I was 10 years old, sitting in a friend’s attic in our eastside Dayton neighborhood. His teenage brother played a 45 rpm single of Elvis Presley singing “(You Ain’t Nothin’ But a) Hound Dog” on a portable record player, and I was hooked.

I felt guilty at the time, recalling that a few years earlier my mom had boycotted the “Ed Sullivan Show” (a Sunday evening ritual) when Elvis made his first TV appearance. I had no idea who Elvis Presley was. I was seven. But in 1956, rock and roll was scary for many parents.

In a way, of course, all this goes back to Thomas Edison’s invention of the phonograph 80 years earlier. Back then, he thought he was inventing a playback dictaphone machine, which would make life easier for clerks taking notation from bosses. He had no idea that his invention would spawn a multi-billion dollar global music business.

Edison was 30 when he patented his phonograph in 1877, but he wasn’t the first to record sound. That happened 20 years earlier, when French inventor Edouard-Léon Scott de Martinville created the “phonautograph” – “a machine that inscribed the vibrations of airborne sounds” and etched grooves into a paper cylinder coated with a black pigment.

“Scott’s phonautograph was an extraordinary instrument,” one Edison historian has noted. “From the beginning of time, sound had been invisible and fleeting. The phonautograph made it both visible and permanent by writing it to paper. In this way sound waves could be studied as never before.”

Edison was unaware of Scott, who hadn’t figured out how to play back his recorded sounds. But Edison’s early phonograph both recorded and reproduced sound. “This was so astounding,” one historian wrote, “that the phonograph singularly established Edison’s international reputation as a prominent inventor.”

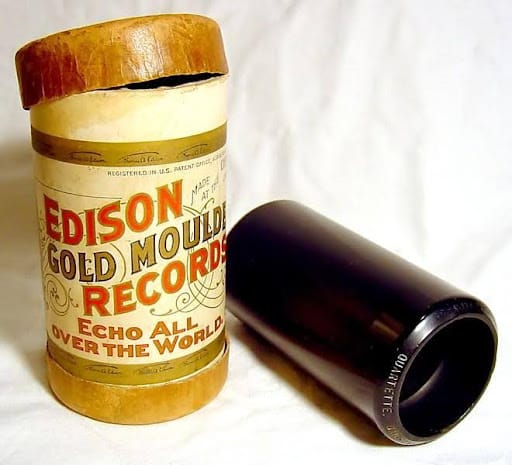

Edison recorded his voice by speaking into a mouthpiece. The sound waves vibrated a needle, which made indentations on tinfoil wrapped around a metal cylinder. Edison then played it back by repositioning the needle to retrace the grooves in the foil. Eventually, more durable wax cylinders replaced the tinfoil. By the late 1800s, music recordings were sold in cylindrical containers featuring Edison’s name.

In 1887, German immigrant Emile Berliner developed a flat disc made of zinc and coated with beeswax. His recordings played on a hand-cranked turntable called a gramophone. The flat disc allowed the mass production of recordings from a master disc which was easier to duplicate than a wax cylinder.

Berliner’s flat disc records had room for a label identifying the recording by title, performer and songwriter, leading eventually to a “star system” where fans could buy the music of favorite artists. The Italian tenor Enrico Caruso became world famous, making more than 250 recordings between 1902 and 1920.

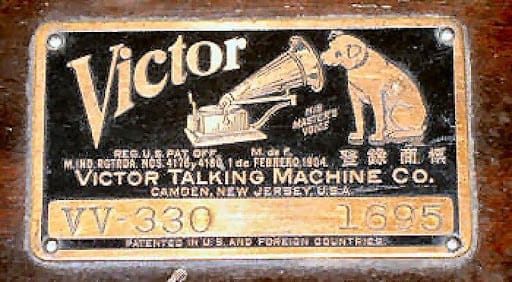

But sound recording would not become a mass medium until inventors figured out mass marketing. That involved putting the guts of an invention inside an attractive package — like a piece of furniture — that could be displayed in homes. That happened in the early 1900s when Berliner hooked up with Eldridge Johnson’s Victor Talking Machine Company. Johnson’s company created the Victrola. By 1913, Johnson was selling 250,000 sets a year, and his company logo became an iconic ad image.

As radio developed as a mass medium in the 1920s, the Victrola fell on hard times. In 1929, the company was sold to the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). When the Depression hit, phonographs and record-buying became non-essential. After all, families could listen to music for free on the radio.

Sound recording as an industry almost collapsed during the Depression, but the jukebox gave the industry a boost. When Prohibition ended in 1933, tavern owners needed a cheaper form of music than live bands. Jukeboxes and booze helped bars limp through the 1930s and World War II. After the war, families throughout the 1950s started buying hi-fi (high fidelity) systems, housed inside buffet-like pieces of furniture that could play both radio and records.

The sound recording industry continued to rebound as inventions built on one another. These included vinyl in the 1940s, audio tape which allowed teens to create playlists in the 1970s, and digital CDs in the 1980s which made former technologies (temporarily) obsolete.

When the digital MP3 format (audio compression file-sharing) came along in the early 1990s, the record industry suffered again as younger consumers started sharing music online without paying for it. Lawsuits ensued. Students were targeted.

In 2001, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the music industry, declaring file-swapping and free music services an illegal violation of music copyrights held by record labels and artists. Two years later, Apple developed iTunes (to accompany the iPod), and for 99 cents you could buy a song online.

Pandora, the first streaming service, began in the U.S. in 2000, offering free music but also an ad-free service for a monthly charge. These charges helped Pandora pay for the rights to the music. But even with nearly 90 million listeners, Pandora didn’t make money until Sirius XM bought it in 2019. Sweden’s Spotify began in 2006 and today is the world's largest music/podcast service with nearly 700 million listeners worldwide — about 200 million paying for its ad-free service.

I prefer Pandora, which my students told me was for “old people.” I pay monthly for my self-designed rock and roll rotations. I still listen to “Hound Dog,” but these days prefer Big Mama Thorton’s 1952 version. When I play Scrabble with Mom in her Dayton nursing home, she prefers the Patsy Cline rotation as our background sound.

Richard Campbell is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media Journalism & Film at Miami University. He is the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.