Media Matters: Newspapers inspire Hollywood

For decades, Hollywood has drawn on both stories told first by journalists and on stories about journalists themselves.

In my years as a department head at Miami, I attended 15 spring commencements. By far the best speaker was Wil Haygood, class of ’76.

In spring 2013, Haygood began his address by showing the trailer for “The Butler” (released later that year), the Hollywood movie based on a story he had written for the Washington Post in 2008. Haygood had found a Black butler, Eugene Allen, who had worked for eight presidents. The story ran in the Post two days after President Obama was elected to his first term. The article led to Haygood’s best-selling book, “The Butler: A Witness to History” (translated into eight languages) and the award-winning film starring Forest Whitaker and Oprah Winfrey. Thanks to Haygood, Whitaker was Miami’s 2014 commencement speaker.

“What was significant to me about the movie — aside from using my journalism skills to track down Eugene Allen, the real-life butler,” Haygood told me, “is that it encouraged people to look up the history of race and the White House in America. We ignore history at our own peril.”

After a long career as a reporter for the Boston Globe and the Washington Post, Haygood left reporting to write books full time, including “Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World” — his ninth book. A New York Times reviewer called the book an “important, spirited popular history. Like a good movie, it pops from the start.”

“Colorization” is now among nearly 400 books targeted by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth for removal from the U.S. Naval Academy Library for being related to diversity, equity and inclusion. More on media censorship in my next column.

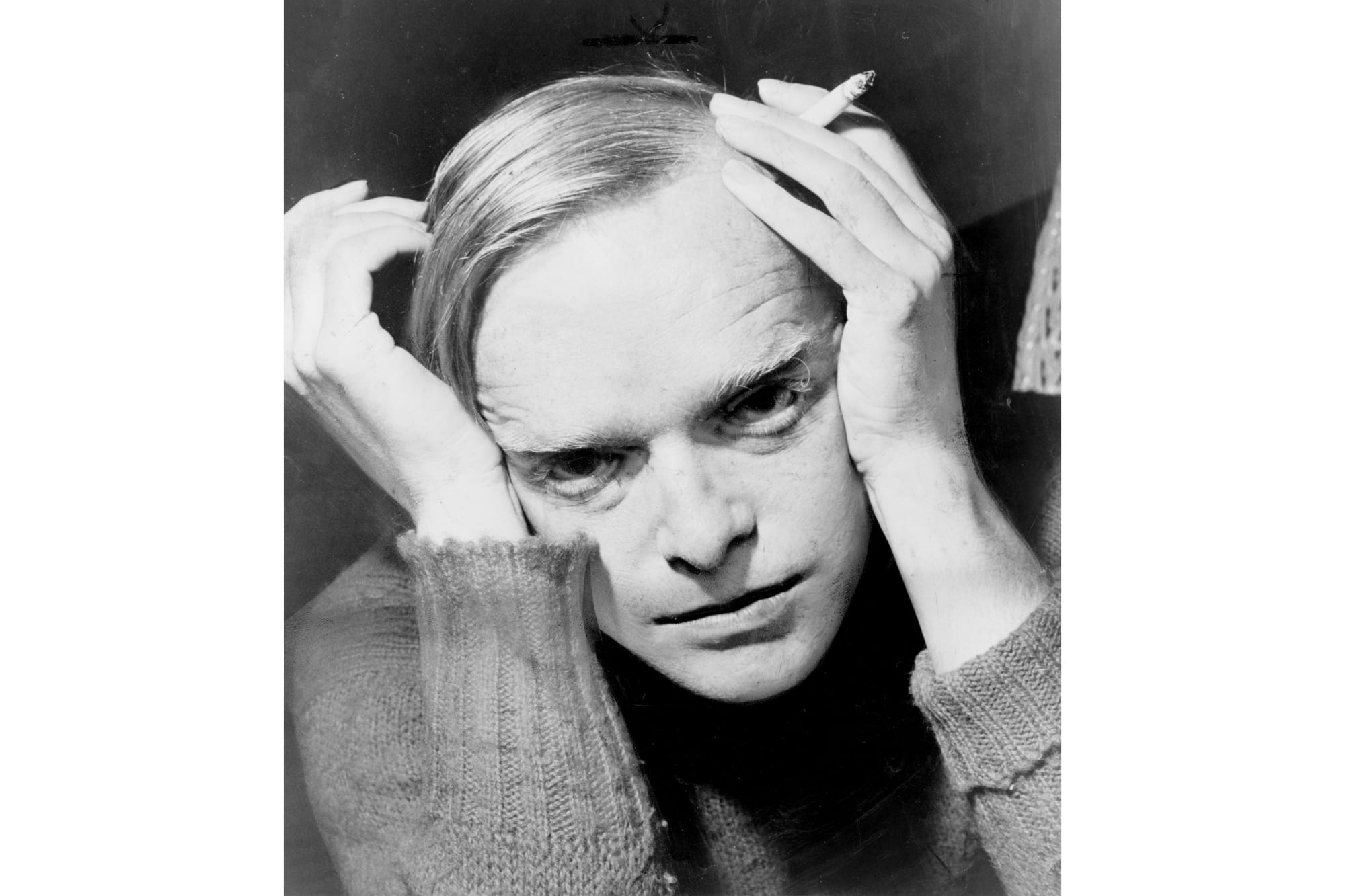

Haygood continues to serve Miami as a distinguished writer and scholar, returning each semester to talk to classes and host an annual film series. Haygood is a film buff. When he taught at Miami, one course featured books that had been turned into films, including “The Butler” and “In Cold Blood,’” based on Truman Capote’s book.

With that book, Capote claimed to have written the first “nonfiction novel,” telling the story of the Clutter family, murdered in their Kansas farm house in 1959. Capote had gotten the idea for the book from a reporter’s crime story, clipped from the New York Times. Capote himself became the subject of the movie “Capote” (2005), about how he researched and reported the story with his friend Harper Lee, who became famous in 1961 as the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “To Kill a Mockingbird.”

Throughout film and TV history, reporters have not fared well, often stereotyped as anonymous pests shoving microphones and smartphones in people’s faces. Still, the hard work of journalism, sometimes called “the first draft of history,” has occasionally gotten its due.

Most famously “All the President’s Men” (1976) was based on Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s book of the same name, detailing their coverage of the Watergate scandal for the Washington Post, documenting the unraveling of Richard Nixon’s administration.

“Good Night, and Good Luck” (2005) marked Georgle Clooney’s directorial debut and depicted in black and white the heroic work of CBS reporter Edward R. Murrow, who took on Joseph McCarthy, the paranoid Wisconsin senator who in the early 1950s spotted communist conspiracies everywhere, including Hollywood and the U.S. Army.

Then in 2015, the movie “Spotlight” was the surprise winner of the Academy Award for Best Picture. The movie tells the story of how the Boston Globe’s investigative team, named Spotlight, reported on the abuse of children by Catholic priests throughout the Boston diocese. It wasn’t until the Globe (then owned by the New York Times) shined a light on the scale of priest abuse that concern spread nationally and then globally. No longer was this just a local problem — a bad priest here, a bad priest there — it was a systemic problem and remains a global tragedy.

Many of us in journalism education show this film routinely. I once had a student come up to me after a viewing to tell me his family was related to Bernard Francis Law, the discredited Catholic cardinal who for years covered up the Boston abuse scandal. He said his family had discouraged him from watching the movie, and he thanked me for showing it.

In addition to Haygood’s commencement speech in 2013, that year Miami’s Media, Journalism & Film department started the Inside Hollywood workshop, taking students to L.A. to meet and shadow Miami alumni working in the entertainment industry.

In one session with a film and TV producer, a student asked, “Where do you get your best ideas?” The producer did not hesitate: “Read newspapers.”

Richard Campbell is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media Journalism & Film at Miami University. He is the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.