Old buildings, new developments and alternative visions

As Oxford develops its first Historic Preservation Plan, Miami University has repeatedly considered razing and rebuilding on historic properties. What happens when towns and universities have competing priorities?

Talk to any developer in Oxford about what it takes to start a new project in town, and they’ll give you a rundown of the whole process required.

Oxford’s zoning code, plus other standards within the Uptown Historic District, lay out the considerations every new building and major renovation needs to uphold. If a developer wants to go above the city’s 48-foot height limit on High Street, build out a property at a higher density than the zoning allows, or construct a sidewalk in a way that doesn’t meet the letter of the law, they’ll need permission.

Most developers in town, that is.

In a 1980 decision, the Ohio Supreme Court found that properties owned by state agencies — such as public universities — aren’t automatically exempt from municipal zoning restrictions. However, the court did not require state agencies to follow zoning procedures or ultimately follow zoning restrictions, so long as they made a “reasonable attempt” to comply.

That ruling has guided the relationship between public universities and the municipalities since it was delivered, including the relationship between Miami University and Oxford.

That relationship will be especially important in the coming years as Oxford works to develop its first Historic Preservation Plan and Miami works to replace Millett Hall.

Brownfield v. State and what it means in Oxford

When the State of Ohio purchased a single-family home to operate as a halfway house for discharged psychiatric patients in Akron, nearby property owners filed a lawsuit. The neighborhood was zoned for single-family residential use, not commercial, and the state didn’t seek approval before creating its halfway house.

The defendants argued that municipal zoning must be secondary to state authority since a state agency could theoretically use eminent domain to acquire the property for public use despite zoning restrictions. In Brownfield v. State, the Supreme Court of Ohio ultimately rejected this interpretation that state developments are “absolutely immune from local zoning laws.”

The court found that the municipality's exercise of its zoning powers and the state's exercise of the power of eminent domain are both intended to accomplish public purposes. However, when those public purposes are at odds, the governments — or the court — need to “resolve the impasse in favor of that power which will serve the needs of the greater number of our citizens.”

Bricker Grayden, a Cincinnati law firm, wrote in a 2019 post that when the local government and the state have competing interests in development, a two-step analysis applies.

“First,” the law firm wrote, “the state is required to make a ‘reasonable attempt’ to comply with the local zoning restrictions,” by locating developments in areas where they are permitted.

What does a “reasonable effort” mean in this case? While public entities may be expected to adhere to general zoning guidelines, they are “not required to ‘follow a locally prescribed set of procedures to obtain the approval of the local zoning agency’” under Brownfield.

For example, Miami didn’t need approval from Oxford’s Planning Commission or City Council to move forward with the McVey Data Science or Clinical Health Sciences Buildings. Even if Oxford had wanted to issue a stop work order, they wouldn’t have had the authority.

The court’s findings don’t apply to requirements like site access, fire safety and building code compliance.

“However, where the state’s conformity to local zoning requirements would ‘frustrate or significantly hinder the public purpose underlying the acquisition of property,’ the courts proceed to the second step of the inquiry and examine its immunity.” Under the Brownfield test, according to the law firm, courts consider several factors to determine whether the state agency is truly exempt from local zoning regulations.

In some cases, a zoning restriction could be impossible for state agencies to uphold.

Universities, school districts and other entities are required to allocate money in specific ways, and if a zoning regulation falls outside that requirement, “the expenditure would be invalid,” Bricker Graydon writes.

How Oxford and Miami work together

Zoning authority aside, Miami and Oxford have collaborated on plenty of projects in the recent past. Those include the College@Elm, an innovation center meant to boost the local economy, and plans to improve the Miami University Airport. Last year, as the Oxford Fire Department faced a significant budget shortfall, Miami agreed to match funds raised by a local levy for the next decade to support the department.

Multiple town-gown groups meet regularly throughout the year. Community Development Director Sam Perry and his staff, as well as the service department, meet with leadership from Miami’s physical facilities department each month to share updates.

Recent meetings have touched on plans for a new arena on Cook Field to replace Millett Hall, but the focus is often on streets, utilities and other services, which the university and the city need to coordinate on.

“We’ve been operating for so long, Miami does what they want to do with their property, and if they need the city to help them, they will let us know,” Perry said. “We have an understanding with each other, and it works.”

As a state institution, much of the permit and application process at Miami happens at a state level, including building and demolition permits. The arrangement circumvents the public hearing process that private developments sometimes have to go through, Perry said, though the university may still do its own studies.

“They have assured us that when those kinds of things come up, if the project they’re planning to do has potential traffic impacts, that they will have that analyzed and let us know what their findings are,” Perry said. “I would trust that that would happen [for the arena].”

Cody Powell, associate vice president for facilities planning and operations at Miami, said the university’s method of engaging with the city isn’t drastically different from private developers.

“If you own a property in Oxford, not everybody consults immediately with the city,” Powell said. “We maintain a great partnership. We meet regularly, we talk about future plans, we collaborate where we can for economic development.”

However, Oxford isn’t always looped in at the beginning stages of decision-making, so Perry said it’s taken time to understand the arena plans. The idea seemed more sudden than how the city makes major decisions, he said. For example, when the city moved its offices to the current Municipal Building, a former library, it took a “pretty lengthy process” to determine feasibility and reasoning.

Communication and in-depth feasibility studies are especially important given how reliant on Miami Oxford is, Perry said. Every decision made by the university impacts the city.

“Oxford is a very small town. It’s a small puddle to drop a pebble in,” Perry said. “The ripples get from one side of the puddle to the other very quickly.”

Competing priorities in preservation

The difference between Miami and Oxford’s priorities has, at times, come into sharp focus, particularly around historic preservation.

This year, Oxford is also working with consultants to develop the city’s first Historic Preservation Plan and to create new historic design guidelines for developers.

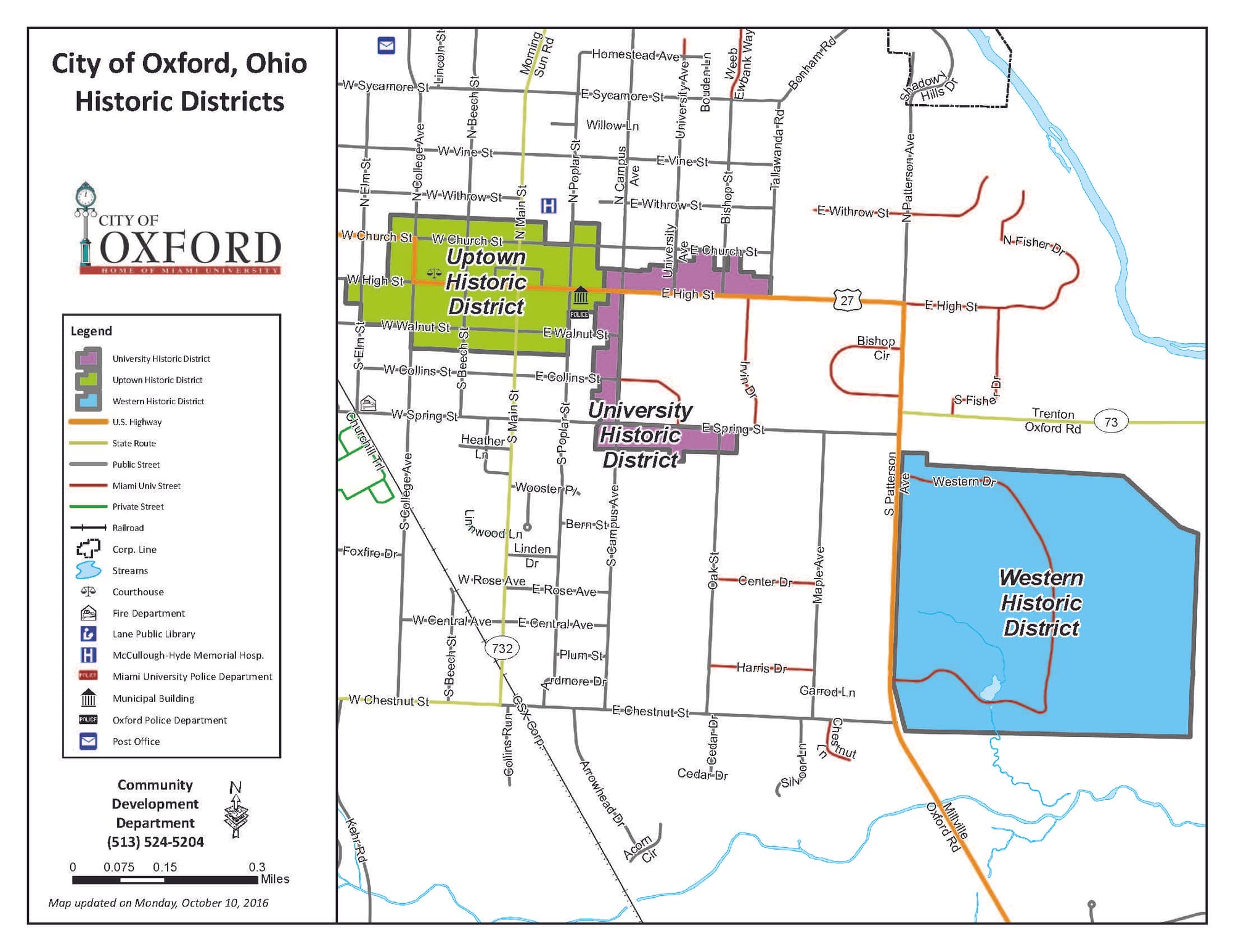

The city has established three historic districts, two of which are almost entirely on Miami University’s campus. The third, the Uptown Historic District, is subject to design guidelines from the Historic and Architectural Preservation Commission (HAPC). When developers want to demolish buildings Uptown, they need permission.

By contrast, when Miami opted to tear down Thomson Hall, a building in the Western Historic District designed by a local architect, the decision never went before city staff.

Similarly, the university didn’t discuss plans to demolish Wells Hall or Joyner House with the HAPC or the city’s community development department before releasing a survey listing the site of those buildings as a potential location for a new arena. Both buildings are within the University Historic District, and the university’s email stated that both are slated for demolition in the future regardless of arena plans. That location also would have called for the demolition of Bonham House, an 1868 building with a historic marker that the university had not previously planned to tear down.

“We offer the process if they want to follow it,” Perry said. “But they’ve never taken up on it since I’ve been here.”

Powell said the decision to tear down old buildings often comes down to cost. Miami maintains roughly 200 buildings, and each one has operational expenses.

“Is historic significance something that we look at? Yes, of course,” Powell said. “But we can’t possibly preserve everything … and so we have to try to determine those buildings or those structures that we think have enough historic significance that we’re going to have to find a way to preserve them.”

If the university wants to renovate older buildings constructed before the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), those renovations need to make the building ADA-compliant. That accounts for part of the cost to renovate rather than replace Millett Hall and was a factor in the demolition of Thomson Hall, a residence hall without elevators.

“You can’t keep every building. It’s impossible,” Powell said. “There’s not enough money. To meet the needs of a modern facility that will support our students today, some buildings just don’t make sense to renovate.”

When plans change

Sometimes, pushback can lead the university to change course. At one point, Perry said, the university considered demolishing Patterson Place, a historic building on Western Campus. Beyond the city’s Western College Historic District, that side of campus is also on the National Register of Historic Places, so when locals and alumni from the Western College for Women pushed back on the demolition plans, Miami changed course.

Numerous responses to the site selection survey also opposed constructing a new arena at the Southwest Quad location. An Oxford Free Press analysis found that more than 100 respondents mentioned history or historic value in their responses.

The university ultimately chose to move forward with Cook Field despite more widespread opposition to that location, citing less demolition costs as part of the motivation. Three of the four buildings that would have been demolished in the Southwest Quad location were all set to be torn down anyway based on “previously designed campus plans,” according to the initial survey email.

Miami receives roughly $21 million every two years from the state to support capital improvements, Powell said. That funding barely scratches the surface of the cost of projects like the $80 million Bachelor Hall renovation or the $96 million construction of the Clinical Health Sciences and Wellness building.

Still, some buildings are worth keeping around despite the expense. Elliott and Stoddard Hall, for example, the oldest residence halls on campus, are priorities to preserve, Powell said.

In some cases, renovations do make the most financial sense. The university originally planned to tear down Rowan Hall and Gaskill Hall to make room for the Armstrong Student Center, Powell said. When the finances didn’t come through, the university adopted a new plan to construct a student center around the existing buildings, leading to the facility that exists today.

Corey Watt is chair of Oxford’s Planning Commission and serves on the HAPC. His alma mater, Western Michigan University, has torn down historic buildings in the past, a trend he wants Miami and Oxford both to avoid.

Last fall, the Oxford Free Press published a map of buildable sites the university had identified for a potential arena, including historic locations like Lewis Place, Bonham House and the green space next to Slant Walk. Watt said that map was revealing for the university’s priorities, even if those sites weren’t ultimately selected.

“I was mortified to see the Slant Walk Green and Lewis Place on the original proposed list, and I’m not much further on Joyner, Wells and Bonham,” Watt said. “These are things we can never get back.”

Maintaining the historic structures of Miami and Oxford is a priority because it defines the town’s character, Watt said. The university and the town are intertwined, and he said decisions should involve all stakeholders.

“People may not have a personal tie to these buildings, but I’m sure they would really notice if they were gone,” Watt said. “Millett has served its purpose … I’m not opposed to a new arena, but that doesn’t mean that we just put it anywhere.”

Miami’s Board of Trustees voted to move forward with plans for an arena on Cook Field at a Feb. 28 meeting. The university will enter a design phase for an “event district” anchored by the arena now, according to a press release from the university.