How does Miami plan for campus development, and is it enough?

As discussions about a new arena at Miami University reached the public last fall, some faculty pushed for a campus master plan to guide future development. The university maintains multiple thematic plans, but no overarching guiding document.

Just after Miami University’s 2024 Spring Commencement, the university broke ground — literally — on a new project in front of Millett Hall.

The project, 500 geothermal wells extending more than 800 feet underground, will use underground heat to power heating and cooling through renewable energy, part of Miami’s commitment to sustainability, according to reporting from The Miami Student.

Those wells also render Millett’s front lawn largely unbuildable.

At the time Miami announced the geothermal project, official communications stated that the well field would help provide clean heating and cooling to buildings including Millett Hall. Now, the university plans to move its basketball and volleyball programs south to Cook Field. In a survey which garnered more than 1500 responses from students, faculty, staff, alumni and community members, hundreds of respondents questioned why the new arena couldn’t be constructed near Millett’s current location.

College campuses across the U.S. are increasingly adopting campus master plans, documents which aim to guide the physical development of facilities for decades in the future. Miami lacks such a plan, though, opting instead for a series of thematic plans focused on specific areas like housing, utilities and circulation.

A guiding document may not have ultimately helped preserve Millett Hall’s front lawn as a desirable building site for projects like a new arena. Some faculty at Miami, though, argue that having an overarching plan that guides broad campus development could help the university avoid impulsive future decisions.

Compartmentalizing planning

Cody Powell, associate vice president for facilities planning and operations, said in an interview prior to the announcement of the final site selection that Miami maintains roughly nine thematic plans. Those include a 2011 circulation master plan, a 2012 utility master plan, a housing master plan and even a stormwater management plan.

When asked if the university remains opposed to developing an overarching plan, Seth Bauguess, senior director of communications for Miami, wrote that the university’s area-specific planning documents “collectively serve as a campus master plan.” “This approach of utilizing multiple, area-specific master plans provides valuable flexibility to the university as it navigates dynamic market factors,” Bauguess wrote.

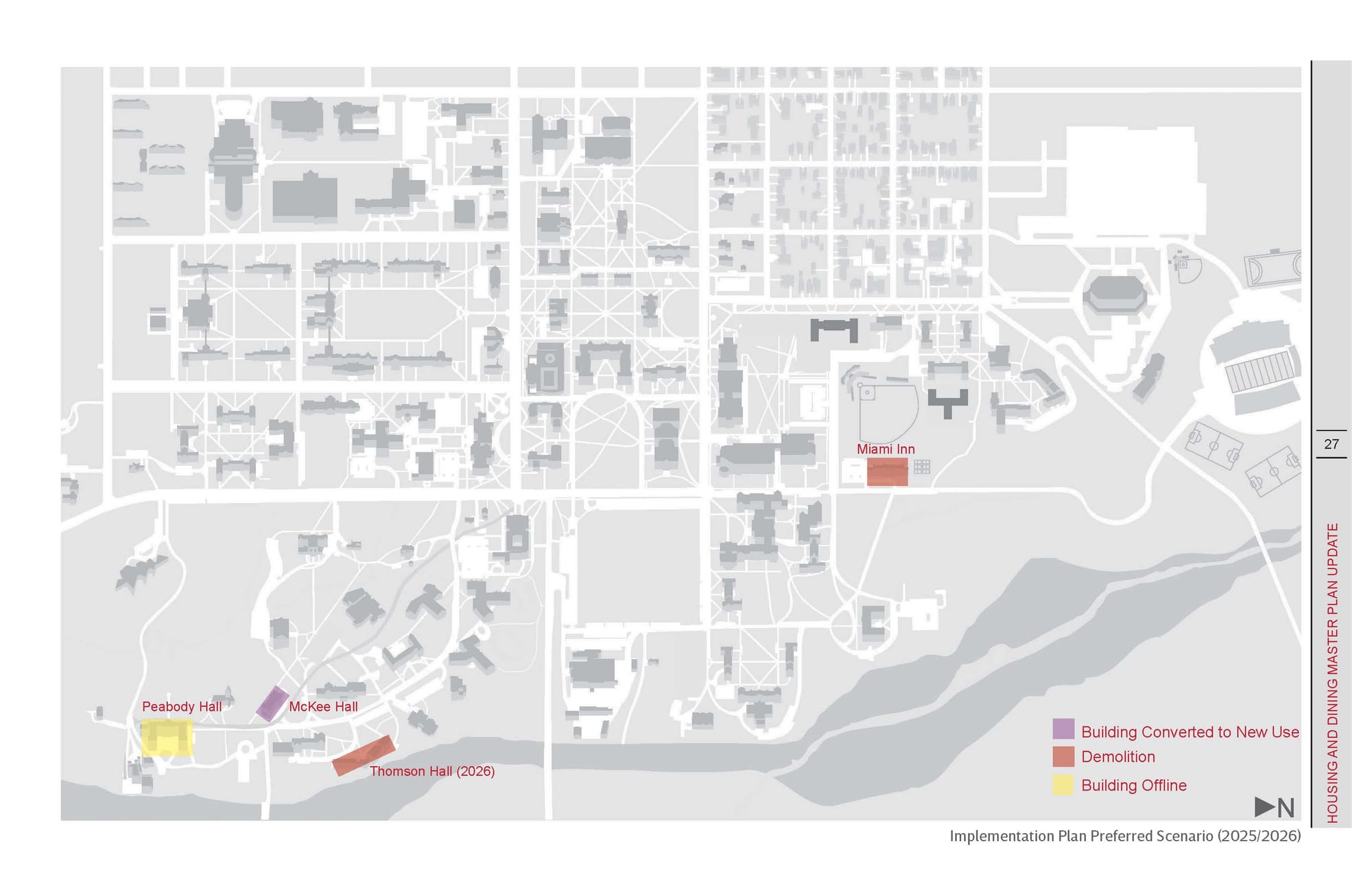

Much of Miami’s development furthers goals laid out in these separate plans. The geothermal wells in front of Millett Hall, for example, build toward a goal laid out in the utilities master plan to convert Miami’s heating to less carbon-intensive methods. Similarly, the demolition of Thomson Hall, construction of Heritage Commons and other residence hall upgrades were all laid out in the housing plan.

Each plan serves a distinct purpose. The 2011 circulation master plan, for example, focuses on improving transportation and parking. While it makes mention of carbon emissions, the focus of the utilities master plan, it doesn’t take into account how facilities like residence halls may change over time — the focus of the housing master plan.

Last November, members of Miami University’s Campus Planning Committee (CPC) — a group of faculty, staff and students who can make recommendations but not enact policies — spoke at a University Senate meeting about the need for an overarching guiding document. The CPC representatives also warned that a list of buildable sites for the arena project included important areas like the green space next to Slant Walk, Lewis Place and Cook Field, the site ultimately chosen.

Kelly Knollman-Porter, associate professor of speech pathology and audiology and chair of the CPC, said during the meeting that the committee had sent a letter to administration to request a campus master plan to guide decision making in 2022.

“They denied that request,” Knollman-Porter said during the meeting. “They said that the financial cost for establishing a campus master plan would be too great at that time.” She added, though, that senior vice president for finance and business services David Creamer said a major update to planning documents would be necessary “if the university … was anticipating a rapid expansion or change on any of its campuses.”

In an email and subsequent follow-up with the Free Press, Bauguess said it is “generally correct” that the university views the thematic plans as collectively representing a campus master plan, and therefore not intend to develop a separate overarching guiding document.

A lone approach among peers

Since Powell began his career as a student intern at Miami in 1994, the university has constructed more than 40 new buildings. If the university tore everything down and started from scratch today, Powell estimates that it would take $4.5-5 billion to rebuild the current facilities, which span over 8.5 million square feet of indoor space.

That’s a lot of money, and a lot of construction. If the university used an overarching plan instead of more focused ones, Powell said, it would be harder for physical facilities staff to adjust to changing conditions.

“These various plans that we have inform us and dictate to us, but a master plan — something that somebody sits down and spends hundreds of thousands of dollars and gets input from people on campus today — we find sits on a shelf and changes fairly quickly,” Powell said.

Still, that leaves Miami as the largest public university in Ohio not to go through the master planning process in the past decade.

The University of Cincinnati is in the middle of a yearlong process to update what it calls the 2024 Physical Campus Master Plan right now, and goes through similar updates roughly once a decade. Ohio State University similarly adopted “Framework 3.0” in 2023, a guiding document that built on other plans published in 2010 and 2017. The resolution adopting the plan described Framework 3.0 as living “alongside the strategic and capital plans of the university to create a shared vision for development while enabling the university to revise and re-envision as future conditions warrant.”

Kent State, Ohio University and Bowling Green State University, which is smaller than Miami, have all gone through similar processes since 2016. OU’s plan looks up to 50 years in the future, and Bowling Green calls campus plans “an incredible tool.”

Flexibility, or haste?

Miami gets minimal resources from the state to help with capital improvement — just $21 million every two years, Powell said. If the university relied on state funding only to fund the new arena project, it could take two decades to get enough money to make it happen.

Despite that, the campus is constantly evolving. Some of the biggest recent projects like the McVey Data Science Building were made possible with large alumni donations, and the university has its own capital improvement fund.

“Campuses change, and during my tenure here, I’ve been shocked at the amount of transformation that occurs on a campus,” Powell said. “The requirements of the facilities to be able to support those changes, I think, are far more dramatic than what people imagine.”

Focusing on thematic plans may allow for flexibility when making changes, but it also has consequences, said David Prytherch, a professor of geography and member of the CPC.

Those consequences can be long-lasting. Prytherch said the CPC asked physical facilities staff if they were confident in the geothermal well location in front of Millett Hall when it was first suggested. The CPC was told yes. Now, the site can no longer be considered for any major building construction projects.

“The university cites cost. They say planning will be costly,” Prytherch said. “I think the absence of a plan can be really costly.”

Making major development decisions one at a time — where to put a well field, then where to put an arena, then how to develop an event district — can lead to more expensive construction in the long run, Prytherch said. The comprehensive process that a campus master plan would call for could help the university consider its resources as a whole instead of in isolation.

Oxford recently completed its own comprehensive plan following an 18-month process with consultants. The resulting document, Oxford Tomorrow, is set to guide decision-making for the next decade or more in town and has already been cited to justify investments and new initiatives in housing, recreation and economic development.

All told, that plan cost roughly $150,000 to develop and engaged more than 800 community members. Miami’s annual revenue budget is more than $700 million.

“Campuses are complex systems,” Prytherch said. “You cannot make one decision in isolation of all the other moving pieces, and that’s what planning enables you to do is to try to make sure all the moving pieces line up.”

Miami is currently contracting with consulting company Bain and Company to lead a strategic planning process, Miami THRIVE, to “guide the university in reimagining Miami to serve the dynamic needs and interests of students.” Nine committees, including one focused on campus beauty and sustainability, have been working to generate recommendations, but much of the focus is on academic offerings and finances.

Most recently, the university has considered new workload policies that would raise expectations for faculty next semester. This process is linked to the arena discussion and a broader need for unified planning, Prytherch said.

“The arena brings into really great clarity some real existential questions about Miami University,” Prytherch said. “Academics at Miami have undergone steady erosion. We haven’t seen raises in years. Humanities and other programs have been slashed. There’s been faculty attrition. There are fewer people in most departments doing more work … all of which is a form of disinvestment in the core academic mission under the guise of fiscal austerity. And then the president proposes a $233 million athletics project.”

Faculty and librarian unions reached an agreement with the university in late February on a first contract which includes retroactive raises for both groups. Before that, faculty hadn’t received raises since 2022.

If the university opts to put more money toward economic development and athletics, and less money toward academic resources and facilities, Prytherch said it will come at students’ expense. That’s especially true given how important the campus aesthetic is to recruitment and the student experience, hew said.

“There are two things that are really core to Miami’s value and our brand and our reputation. One is the quality of the educational experience, and two is the beauty of our campus,” Prytherch said. “If anything’s sacred at Miami, those things have been pretty sacred. This arena project cuts at both of those things.”

Prytherch isn’t opposed to replacing Millett. “We would like to see an updated arena,” he said. But the process that’s played out over the past several months hasn’t given him confidence that the university values stakeholder feedback in the way a full planning process would call for.

The site selection committee had no student members and just one faculty member. It operated independently of the CPC, which is described by the university as representing the University Senate “in the process of planning and maintaining the physical plant of the institution.” The faculty member on the site selection committee is chair of the CPC.

The arena project may be the largest capital improvement project in the university’s history, yet it went from rumors to a finalized location in just five months. The only formal input from students so far came in the survey sent out by the site selection committee. Despite widespread opposition to Cook Field, that location was ultimately chosen.

“By any standard, it’s being rushed,” Prytherch said. “Maybe it’s a foregone conclusion, but I think as faculty, students, parents and alumni … I think they all have a voice.”

Miami’s site selection survey garnered more than 1500 responses. A change.org petition against the Cook Field location had garnered nearly 3,000 signatures by the time the Board of Trustees voted to move into the design phase Feb. 28. In a press release, the university said the arena will anchor a new “event district” on Cook Field.