Nellie Bly’s legacy and the decline of investigative reporting

Nellie Bly broke barriers for women in journalism in the late 1800s and inspired a new wave of investigative journalism. As the press industry has contracted in recent decades, investigative jobs have been on the line.

As a high school English teacher in Milwaukee in the mid 1970s, I used to paint houses when school was out. But inspired by the Washington Post’s investigation of the Watergate scandal that brought down the Nixon administration, I started working as a reporter in the summers instead – first at a weekly suburban paper, then as a summer intern at the Milwaukee Sentinel, where I was eventually offered a full-time job.

A reporter’s hours for a morning paper were 2:30-11:30 p.m., and my wife and I had a 1-year-old. I needed a job with better hours … and I wanted to study media history. So I commuted to Chicago two days a week to earn a Ph.D. at Northwestern and ended up teaching journalism.

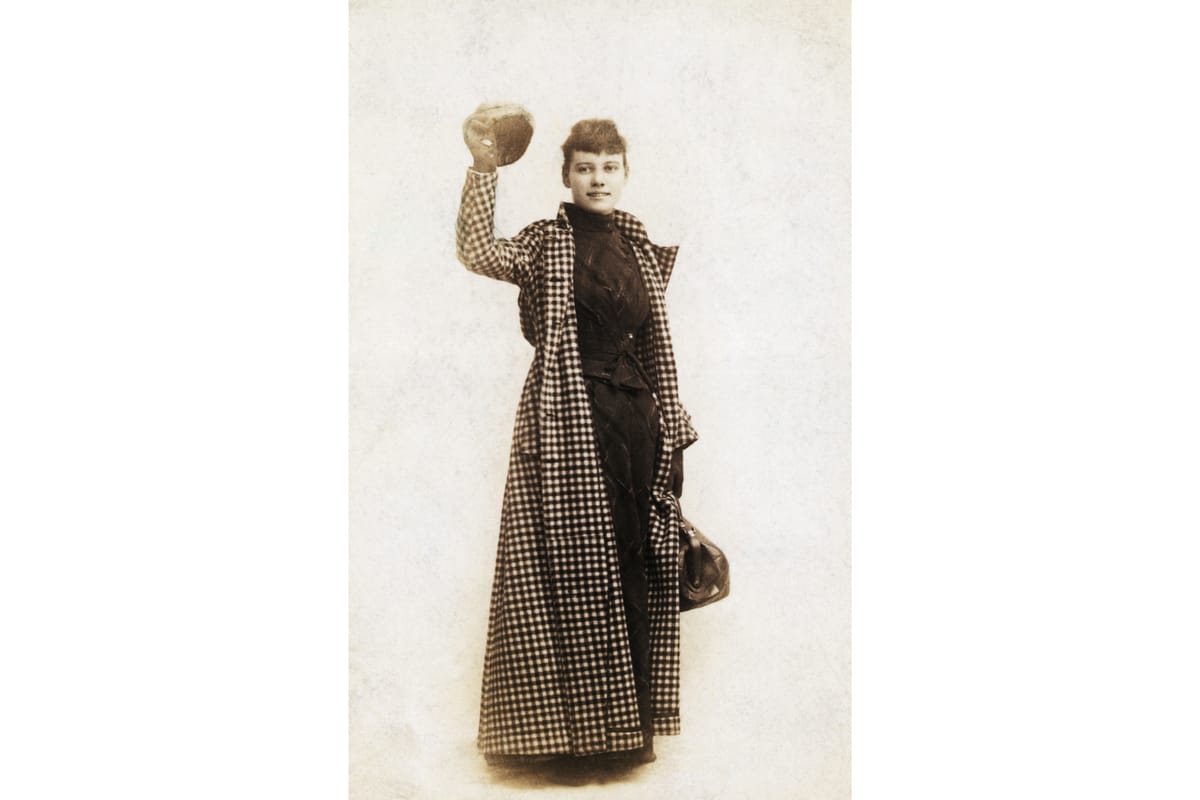

Watergate led to a boom in students interested in the exploits of investigative reporters. My favorite story was about a young woman who worked at the Pittsburgh Dispatch in the 1880s, a time when it was difficult for women to get hired as reporters. It was also considered “unladylike” for women journalists to use their real names. So the Dispatch editors, borrowing from a Stephen Foster song, dubbed her “Nellie Bly” instead of using her real name, Elizabeth Cochrane. When factory owners complained about her stories about poor working conditions, her editors assigned her to society news and to answering letters to the editor. So in 1887, at age 23, she left Pittsburgh for New York City. She wanted to be on the front page.

After four months of persistent job-hunting and freelance writing, Nellie Bly earned a tryout at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, then the nation’s largest paper. Her assignment: Investigate the deplorable conditions at the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island. Her method: Get herself declared mad and committed to the asylum.

After practicing the look of a disheveled lunatic in front of mirrors, wandering city streets unwashed and seemingly dazed, and terrifying her fellow boarders in a New York rooming house, she succeeded in convincing doctors and officials to commit her. Other New York newspapers reported her incarceration, speculating on the identity of this “mysterious waif,” this “pretty crazy girl” with the “wild, haunted look in her eyes.”

Her two-part story appeared in October 1887 and caused a sensation. She was the first reporter to pull off such a stunt. Bly was in the asylum for 10 days. Her dramatic first-person accounts documented harsh cold baths (“three buckets of water over my head — ice cold water — into my eyes, my ears, my nose and my mouth”); attendants who abused and taunted patients; and newly arrived immigrant women, completely sane, who were committed to this “rat trap” simply because no one could understand them. After the exposé, Bly was famous. Pulitzer gave her a permanent job, and New York City earmarked $1 million for improving its asylums.

Within a year, Nellie Bly had exposed a variety of shady scam artists, corrupt politicians and lobbyists, and unscrupulous business practices. Posing as an “unwed mother” with an unwanted child, she uncovered an outfit trafficking in newborn babies. Disguised as a sinner in need of reform, she revealed the appalling conditions at a home for “unfortunate women.” A lifetime champion of women and the poor, Bly pioneered what was then called “detective” or “stunt” journalism.

Her work inspired modern investigative journalism from Ida Tarbell’s exposés of oil corporations in 1902 to 1904 to Hannah Dreier’s 2024 Pulitzer Prize-winning series in the New York Times on widespread use of child labor in the U.S. Dreier’s work exposed both corporate and government failures that helped perpetuate the exploitation of children.

With the loss of 3,300 newspapers and two thirds of daily newspaper reporters since 2005, investigative journalism has taken a big hit. Ariana Huffington, founder of HuffPost, noted a few years ago that as “the newspaper industry continues to contract, one of the most commonly voiced fears is that serious investigative journalism will be among the victims of the scaleback. And, indeed, many newspapers are drastically reducing their investigative teams.” So when metro newsrooms like the Cincinnati Enquirer go from nearly 300 reporters in the 1990s to fewer than 80 today, of course papers can no longer afford the luxury of reporting teams spending weeks on costly investigations that involve large time commitments.

“The print magazine and the print journalism industry is obviously in a great deal of trouble, and one of the things that happened when the business started to give way to the internet and to broadcast television is that a lot of organizations started cutting specifically investigative journalism.” – Matt Taibbi, investigative reporter, Rolling Stone Magazine

Today, national nonprofit outlets like ProPublica and the Marshall Project, sponsored by philanthropic donors, can support serious investigative work at the national level. But regional and small market news outlets can no longer afford to do work that requires months of serious investigation before a final series can go to print.

When I was teaching, I used to show the great films about investigative reporting, including “All the President’s Men” and “Spotlight,” the Oscar-winning 2015 film about the Boston Globe’s team coverage of sexual abuse by priests. Investigative reporting in that case spotlighted a global problem, revealing that abuse in the Catholic Church was systemic and not just a matter of a “bad egg” in a parish here or there. If good regional newspapers can no longer do this kind of work, we will be less informed and the central issues of the day – like climate change, income inequality and the loss of local news – will go under-reported at best and uncovered at worst.

Richard Campbell is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami. He is the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.