News in a fractured media market

Advertisers have spent $390 billion in the U.S. this year. Unlike in the past century, though, only a sliver of that funding has gone toward print media as the market has continued to diversify.

“Information has become a form of garbage, not only incapable of answering the most fundamental human questions but barely useful in providing coherent direction to the solution of even mundane problems.”

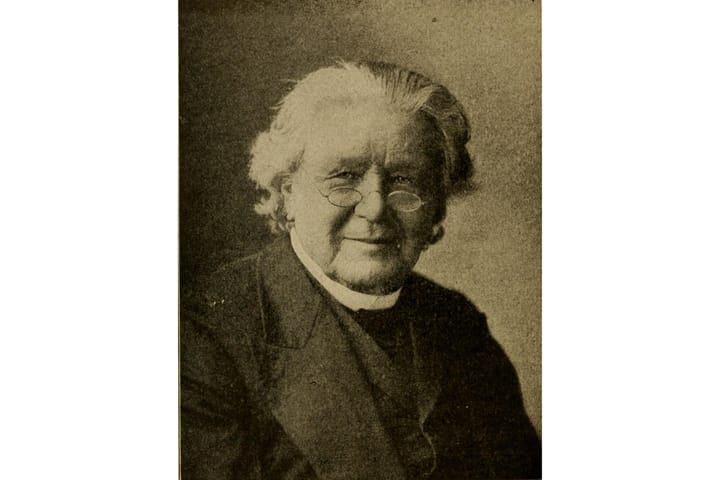

Cultural critic Neil Postman wrote this — mostly about TV ads — in the early 1990s, way before social media and Google’s YouTube started eating up large chunks of our time. Postman, who died in 2003, reminded us that the problem of the 19th century was “not enough information,” while the problem of the 20th century became “too much information.”

While we can avoid much of the “garbage” by using ad-free streaming services, anyone who watched cable and network football games before the election got a plentiful portion of political ads. The cost of these 30-second dystopian melodramas, $11 billion in total, could have instead helped address U.S. wealth disparity. These ads certainly provided no “coherent direction to the solution of even mundane problems.”

Newspapers, of course, are another form of information and, at their best, provide “coherent direction,” telling us what’s going on in our town, state, nation and the world. Newspapers became a mass medium in the mid-1800s after rotary presses made it possible to print thousands of copies in minutes and sell them for a penny. Ads and subscribers made publishers rich. At the beginning of the 1800s, publishers did well if they had 1,000 subscribers. By the end of the 1800s, Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst both ran New York papers, each with circulations over 500,000.

In the 20th century, with the rise of cable and then social media, the old mass media market began to dissolve. Cable TV developed fully in the 1980s by doing the same things that magazines did 30 years earlier with the advent of TV: they specialized and targeted specific consumers rather than a mass audience. The History Channel, the Golf Channel, Hallmark, Lifetime and ESPN, among hundreds of others, began to challenge the network dominance of ABC, CBS and NBC. Ruport Murdoch made it more political when he started Fox News in 1996, targeting conservatives.

Then social media arrived with the World Wide Web. In this climate, with craigslist, ebay and realtor.com leading the way, classified ad revenue for newspapers began to dry up. For-profit newspapers started to disappear: 3,200 now shuttered since 2005, including the old Oxford Press.

In 2024, projections show $390 billion being spent on U.S. advertising, of which only a sliver goes to the print news. Back in 2000, newspapers captured more than 30% of all U.S. ad revenue. Today they get less than 2%, with 77% of that U.S. ad pie going to digital advertising. Google and Facebook alone now gobble up more than half of that.

The ABC, CBS and NBC 30-minute news programs once combined to reach nearly 50 million viewers each evening in the 1970s, but today barely reach 15 million. CBS’s “60 Minutes” alone typically had 40 million viewers on a Sunday evening in the late 1970s. Today that program, still often ranked among the most watched network programs, attracts around 9 million viewers each Sunday.

In our fractured marketplace, we are no longer sharing or seeing the same news. We tend to live in information bubbles, and in a fragmented market it's much easier to sustain confirmation bias: seeking out stories and information that affirm and support our social, political and cultural tastes.

There really is no mainstream media today. Audiences are dispersed, each of us doing our own thing, taking care of our families, going to school, doing our jobs. We are also managing Facebook and Instagram pages, streaming Netflix and Amazon Prime, and watching our favorite specialized cable channels. Even the old networks, ABC, CBS and NBC still do OK in a dispersed marketplace where their viewers are just a quarter of what they used to be. A quarter of 40 million viewers is still 10 million, and a political advertiser will pay a ton for those eyes.

The most watched programs today with more than 20 million viewers are Sunday and Monday night football on NBC and ESPN. It now costs $1 million to buy a 30-second ad spot during these games. It’s easy to see how our political parties spent $3 billion on presidential TV ads alone in 2024.

So let’s return to Neil Postman. He had this to say 40 years ago about TV ads in his 1985 book, “Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business”: “The television commercial has been the chief instrument in creating the modern methods of presenting political ideas.”

Not much has changed.

Richard Campbell is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami.