Reflections: Bob, Pete and me

When columnist Allan Winkler went to see "A Complete Unknown," the movie brought up both personal and cultural memories.

A few weeks ago, I went to see the marvelous new film about Bob Dylan — “A Complete Unknown.” I had seen Dylan perform live a couple of times in the early 1960s, had played his records endlessly in my college dorm, and, in subsequent years, had performed most of the songs in the film, either with my folk group, the Mudlick Five, or in solo shows.

I was overwhelmed with how much Timothée Chalamet sounded like the early Dylan and impressed to learn that he hadn’t played the guitar at all before preparing for the role. Likewise, I was impressed with Monica Barbaro as Joan Baez, both for her singing and her guitar accompaniment.

But I was most intrigued by Edward Norton’s performance as Pete Seeger. A decade ago, I wrote a biography of Pete. As I worked on the book, I visited him in his home in Beacon, New York about 30 times, interviewed him, chopped wood with him on his lot and played music together each time — him on banjo, me on guitar.

It was a heady experience, and while I never knew Pete personally in the mid-1960s, I knew what he had always been like. I’d seen him in film clips and in performance, and Wood got his portrayal just right.

As much as I enjoyed watching the early Dylan as his life unfolded in the film, I couldn’t help but think about Pete and all he had done over the past 60 or 70 years.

He had a powerful sense of what this country could be and should be. He sang with the Weavers, and earlier the Almanac Singers, about the integrity of working men and women. He was tireless in his support of civil rights, and was responsible for the song “We Shall Overcome” that became the marching song of the movement. He took Bob Dylan down South for the first time, and Dylan once called him a “living saint.” He was fervently opposed to the war in Vietnam. Perhaps most impactfully, he advocated for the Clean Water Act and embarked on a campaign to clean up the polluted Hudson River, which succeeded beyond anyone’s expectations.

One of my favorite Pete stories is about him marching in a protest in New York City, up by Columbus Circle, as an old man, carrying a sign. An onlooker yelled out, derisively, “Do you think you’re going to change the world with that sign?”

“No,” Pete replied, “but I’m going to make sure the world doesn’t change me.”

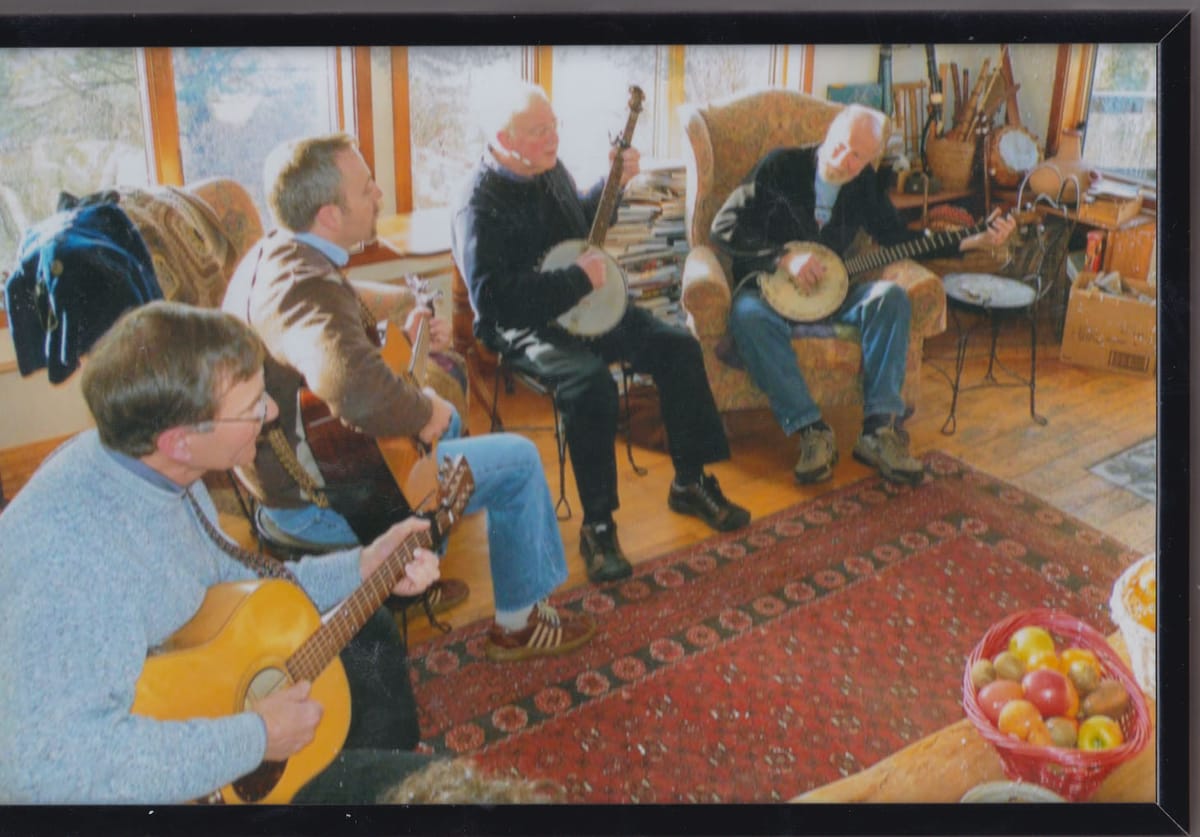

I took my wife Sara to see Pete a number of times, and he and his wife Toshi were always welcoming. I took my sister Karen, a lifelong fan, there on one occasion. And I brought friends with me to play music with Pete. The picture here shows Pete with Dan Cobb, then a young Miami University colleague, Dick Polenberg, an outstanding American historian at Cornell, Pete and me. Just playing music, with two banjos and two guitars, fire blazing, looking out over the Hudson River. It doesn’t get any better than that.

After my book, dedicated to Pete’s wife Toshi, was published, I taught a seminar on folk music at Miami. Midway through the semester, I decided to take my 15 students to Beacon to see Pete. Miami helped with funding. We flew to New York and drove up to Beacon, spending an absolutely memorable day with Pete and Toshi. Later, Donna Boen of The Miamian did a lovely story about our trip.

The film “A Complete Unknown” sparked a lot of memories for me, most importantly about one of the finest figures I have ever known.

Allan Winkler is a University Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus at Miami University, where he taught for three decades. He serves on the Board of Directors for the Oxford Free Press.