Reflections: Boxing

Columnist Allan Winkler's connections to boxing stretch from a meeting with Muhammad Ali to a current boxing program in Oxford which helps people with Parkinson's Disease.

As I was growing up, I watched occasional boxing matches on TV with my father. He was hardly a boxing fanatic, but enjoyed following Rocky Marciano, then Floyd Patterson, and finally Muhammad Ali. And so did I.

At the height of the Vietnam War, Ali was stripped of his heavyweight crown for resisting the draft. “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” he said, and even more pointedly, “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.” His conviction for draft resistance was a travesty, of course, and eventually the Supreme Court struck it down.

And then, on March 8, 1971, as he made his comeback, Ali fought Joe Frazier for the heavyweight title in Madison Square Garden in New York City.

My father, an administrator at Rutgers University at the time, was one of the people given ringside seats for that fight. For him, it was an extraordinary and exciting experience, even though he was disappointed Ali lost.

A decade and a half later, when I came to Miami, I got to know a younger colleague, Elliott Gorn, whose first book “The Manly Art: Bare-Knuckle Prize Fighting in America” was an elegant treatment that rekindled my own interest in boxing.

Then Elliott went a step further. In 1992, he organized a symposium here in Oxford on Ali’s impact on American culture. He invited a dozen top scholars to come and speak. And then, on an impulse, he invited Ali to come and observe.

Much to his surprise — and delight — Ali came and sat through two days of talks. When it came time for a final dinner, Elliott didn’t have room in his own house, and asked me to host it. I was happy to comply.

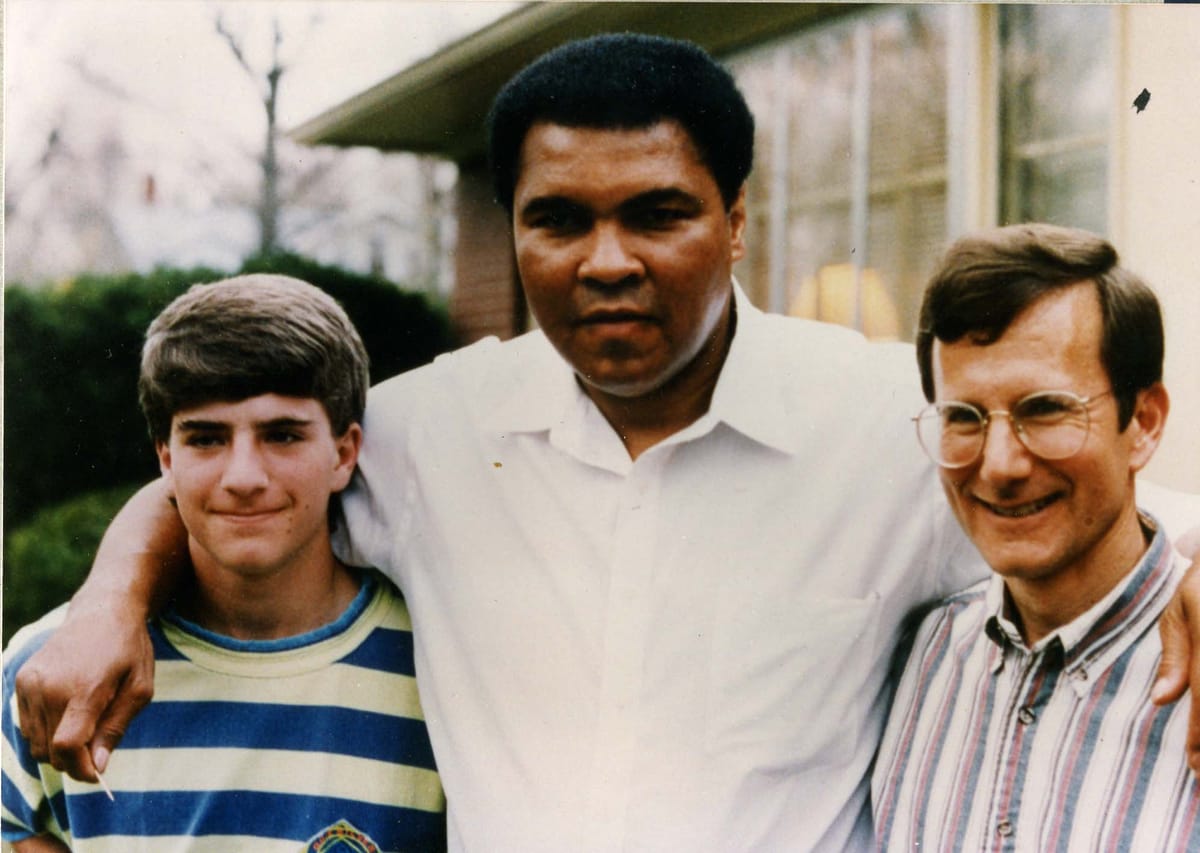

I invited my father and step-mother to attend, and they were thrilled. My son David was home, and he attended the dinner, too.

Ali, already suffering from Parkinson’s Disease, likely from all the blows to his head in his boxing career, still told jokes and performed magic tricks for the dozen and a half guests there. It was exciting to have him with us, and at the end of the evening, he agreed to a photo of David, him and me, by our front door, and that picture is still important to me.

Elliott later published a book of the papers from that symposium, called “Muhammad Ali: The People’s Champ,” and dedicated it to Ali himself.

This foray into memories of boxing leads me into another somewhat different excursion into the world of boxing.

A program called Rock Steady Boxing, established In Indianapolis but now present all over the United States and around the world, reaches out to people with Parkinson’s Disease.

Parkinson’s is a relentless, miserable disease — progressive, incurable and difficult to endure. Actor Michael J. Fox is probably the most famous personality with the disease, but there are thousands, even millions, of others. While there is no cure, the only thing that can slow its progress is exercise. That’s where Rock Steady Boxing comes in.

Participants wear boxing gloves, ranging from black to hot pink. They don’t hit each other but use various bags to increase strength, coordination and stamina.

There was a Rock Steady Boxing program in nearby Richmond, attended by a number of Oxford residents. They then approached Miami University, which agreed to establish a program here, and it worked beautifully for two years. When the Richmond folks pulled out, for their own reasons, a group of Oxford residents approached both Miami and McCullough-Hyde Memorial Hospital, and they agreed together to establish a program which is now operating in the Chestnut Field House three mornings a week. That program is an overwhelming success.

Boxing has been part of my life. I still recall watching occasional matches with my father. I remember having Muhammad Ali in my home. And now I take even more pleasure seeing how boxing — in a different form — can be so important to people I know.

Allan Winkler is a University Distinguished Professor of History Emeritus at Miami University, where he taught for three decades. He serves on the Board of Directors for the Oxford Free Press.