Hi-tech in 1800s: Tales of the telegraph

Communication across the globe is instantaneous today. That reality was brought on by the invention of the telegraph in the 1800s.

“The Young Riders,” a Western show about the Pony Express, ran from 1989 to 1992 on network TV, outlasting the lifespan of the actual Pony Express, which operated for 18 months in the early 1860s. Poor ratings killed “The Young Riders.” The telegraph killed the Pony Express.

Before the telegraph, the only way to send messages over long distances involved drum beats, smoke signals, semaphores, bicycles and the Pony Express, a mail service of horseback riders who delivered letters relay-style. Each method was susceptible to weather.

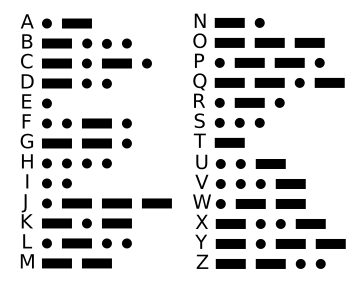

To solve this problem and deliver information in a timely manner, a number of inventors in the 1830s and 1840s, mainly from England, Denmark and the U.S., worked on electric telegraphy. Samuel Morse and his assistant Alfred Vail would get the bulk of the credit after inventing Morse Code. With a $30,000 grant from Congress, Morse — from the chambers of the U.S. Supreme Court — sent the famous 1844 telegram to Vail in Baltimore: “What hath God wrought?”

If we want to assign blame or give credit for “what God hath wrought” in our digital age, let’s start with the telegraph. After all, the Morse Code system of relaying messages via a simple binary system of dots and dashes is the template for the internet era — communicating words and images through the binary codes of zeroes and ones.

“The telegraph is the first attempt to apply electricity scientifically to human communication,” Morse wrote. Using this code, dots were simply a quick interruption of an electrical circuit and dashes a longer interruption.

Telegraphy also initiated some of the great architectural feats of the 1800s. By 1861, the Western Union Telegraph Co. had built the first transcontinental telegraph line across the U.S. After several failed attempts, the U.S. and Great Britain, using a giant steamship, laid the first transatlantic cable running along on the ocean floor between Newfoundland and Ireland. It was completed in 1866 and relayed messages until the mid-1960s. Over the next 75 years, 40 more cable lines were laid along the ocean floor connecting the U.S. to Europe.

Telegraphy made substantial contributions to technological progress and cultural change. As communication scholar James Carey noted, the telegraph “permitted for the first time the effective separation of communication from transportation,” allowing “symbols to move independently and faster than transportation.”

“The telegraph annihilates both time and distance,” Morse once said, and it significantly changed the way businesses, the military and politics operated.

Early on, the newspaper business saw the advantages of relaying news from city to city almost instantaneously. With the transcontinental cable in place, papers wired news from coast to coast. In 1846, newspaper publishers founded the Associated Press wire service, a news cooperative, allowing papers across the country to share breaking stories, report election results and track business deals. The British news service Reuters was founded in 1851, the year Britain completed a cable under the English Channel, connecting London and Paris.

Carey wrote that the telegraph “led to a fundamental change in news. It snapped the tradition of partisan journalism by forcing the wire services to generate ‘objective’ news, news that could be used by papers of any political stripe.” Because telegraph companies charged customers by the word, sending messages was expensive, so flowery language in the news had to go. Adjectives and adverbs were abandoned. The traditional news “lede,” the “inverted pyramid,” got its start in part because of telegraphy. Beginning stories with the most important information — who, what, when, where — ensured that the key parts of the story actually got through. This was particularly important during the Civil War when Union and Confederate armies often cut telegraph wires to disrupt messages.

Abraham Lincoln was the first “wired president” to communicate directly with generals in the field. He’s also known to have sent a $4,000 telegraph to Nevada about its statehood, a message that would have cost $60,000 in today’s money. During the Civil War, the Union’s Military Telegraph Corps erected more than 15,000 miles of telegraph lines. A special office was installed in the War Department next to the White House. Lincoln sent over 1,000 telegrams during the war, hanging out with the operators, sometimes sleeping on a cot during major battles. After the announcement of a Union victory in 1863, Lincoln served a round of beers to the operators. Historians say that Lincoln’s embrace of this new technology gave the North a significant edge.

The telegraph began to decline in 1876 when Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone. The phone of course did not require a code to decipher the text. Then came wireless telegraphy (using Morse Code at first), allowing voice messages to be sent via radio waves and the electromagnetic spectrum. The wireless allowed ships at sea to receive messages, for example, that a war had ended and it was time to head home. Before the wireless, battles could extend for months before naval commanders learned that a peace treaty had been signed.

Western Union sent its last telegram in 2006 but still operates over 4,000 offices worldwide for money transfers. Without the telegraph, would we have electronic money transfers? What about fax machines, cell telephones, emails, communication satellites, the internet? Who knows?

Certainly the telegraph’s contributions to technical progress were far reaching, as inventions build upon one another. But back in the day, Charles Dickens (1812-1870) offered a cautionary take: “Electric communication will never be a substitute for the face of someone who with their soul encourages another person to be brave and true.”

Richard Campbell is a professor emeritus and founding chair of the Department of Media, Journalism & Film at Miami University. He is the board secretary for the Oxford Free Press.